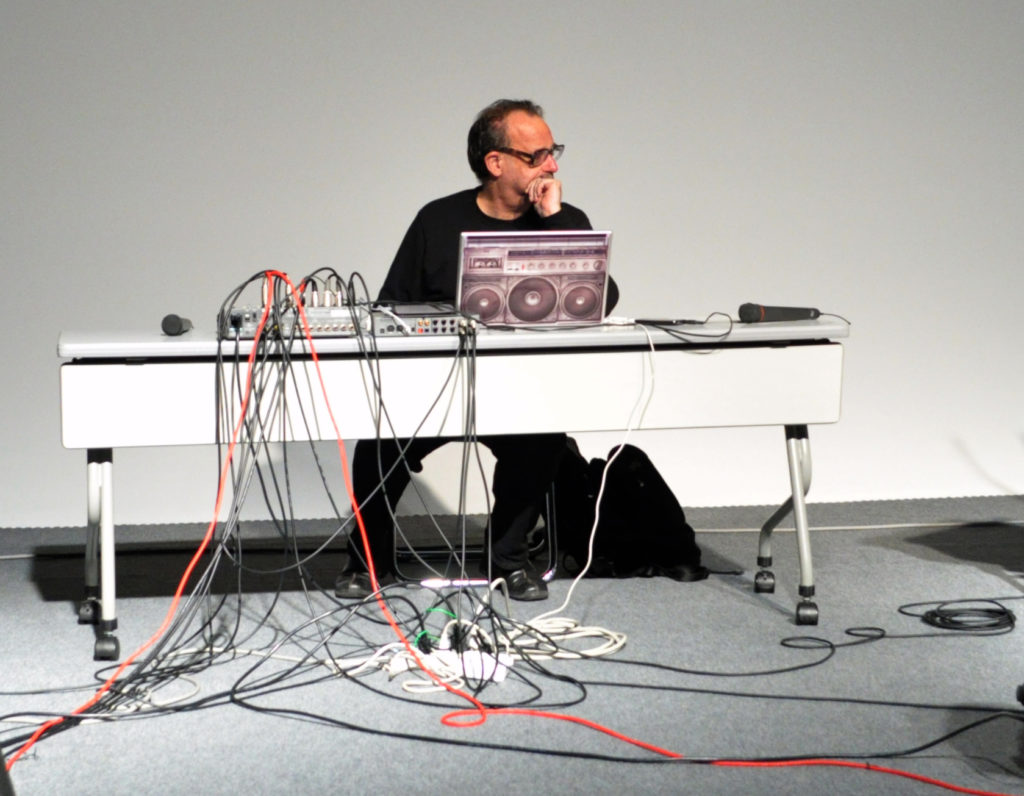

Carl Stone is one of the pioneers of live computer music. He studied composition at CalArts with Morton Subotnick and James Tenney and has composed electro-acoustic music almost exclusively since 1972. He was among the vanguard of artists incorporating turntables, early digital samplers, and personal computers into live electronic music composition. An adopter of the Max programming language while it was still in its earliest development at the IRCAM research center, Stone continues to use it as his primary instrument, both solo and in collaboration with other improvisers. In addition to his work as a composer, Stone served as Music Director of KPFK-FM in Los Angeles from 1978-1981, director of Meet the Composer California from 1981-1997, and President of the American Music Center from 1992-1995. He is currently a faculty member of the Department of Media Engineering at Chukyo University in Japan. His most recent retrospective compilation, Electronic Music from the Eighties and Nineties, is out now on Unseen Worlds and can be purchased here.

Interview by Christina Vantzou and John Also Bennett, who recently collaborated as CV & JAB on Thoughts of a Dot as it Travels a Surface.

———————————————

CV: How long have you been living in Japan?

CS: It’s coming up on seventeen years. I’ve been coming to Japan since the 80’s to work on projects, and in the spring of 2001 I got a six month residency at IAMAS, a media art institution in the middle of the country. While I was there I was offered a job as a professor at a university, so I kind of never went back to the US.

JAB: So you live in Tokyo–what are you teaching there?

CS: Well, the job that I was offered in 2001 actually wasn’t at a music school or even an art school. I’m was in the media department of the School of Information Science, which is now a straight ahead School of Engineering. I’m teaching things like music technology, programming for music, sound design, and acoustic aesthetics. I’ve recently started guest lecturing at Tokyo University, where I teach a course on music technology, and it’s also geared towards programmers and people in the sciences than towards artists.

JAB: You’re mainly working in Max/MSP now, right?

CS: Yes. I don’t know a lot of other programming languages. Max/MSP is one that I specialize in. (laughing) I’m a monoglot.

JAB: Have you always worked with emerging technologies in your music, or was there a period before you started using computers where you were like, playing a saxophone?

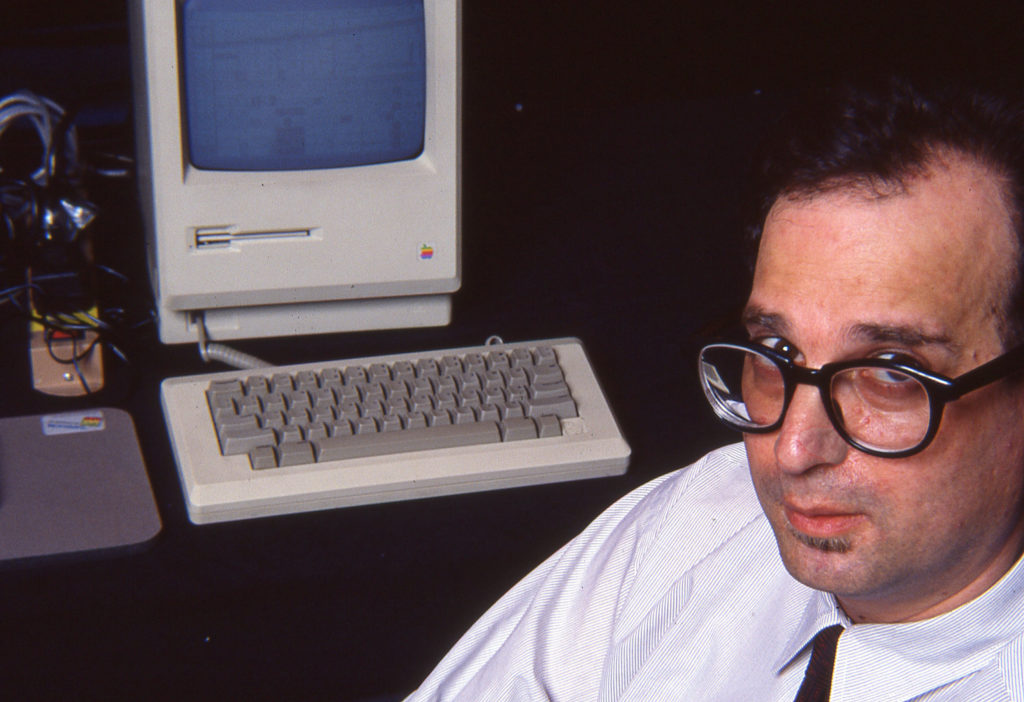

CS: I studied piano from the age of five, but I wasn’t very good and didn’t like practicing, so it didn’t go that far. But then in junior high and high school I played in some bands. I played with the musician Z’EV who you may have heard of—he sadly passed away recently. He played drums, I played keyboards, and we had a bass player by the name of James Stewart. The three of us were a power trio: organ, bass, and drums. No vocals. I played washboard and drums in a jug band, so I have an instrumental background, but I switched to using synthesizers when I first started college in 1969. After that I started performing with turntables, which wasn’t necessarily cutting edge technology, since turntables had been around for quite awhile, but people weren’t really using them in live performance in those days. When the personal computer came along and became smaller and practical, I started using that in the 80’s.

CV: And you studied at CalArts?

CS: Yes, that’s right. My teacher was Morton Subotnick.

CV: I read that while you were there, you started working with samples when you had a job transferring LPs to cassette.

CS: Yes! (laughing) Using found music was a starting point. I wasn’t sampling while I was doing that, I was just fulfilling a job backing up LP records. But it gave me the spirit of the idea, because I was noticing these sound collisions and combinations. I would have two or three different turntables playing all at once while I was doing these backups, so I noticed that it was interesting and I got the idea to try different combinations in my own music, to make new contexts for familiar music or unfamiliar music. That’s what got me off the launching pad, even though I wasn’t really composing at the time–I was just doing my job.

CV: Did you ever use any of the material from the job in your music?

CS: Well, there were a few of those records which I had never heard before that stuck with me and they do end up showing up in later works. For example, there was a great release of music from Burundi and I really fell in love with that album. The sample that I used from that album actually shows up as a starting point for my piece called “Banteay Srey,” which I wrote 15 years later and is part of the release that’s coming out on Unseen Worlds pretty soon.

JAB: That’s amazing. That’s the first piece on the record, I think? It’s a vocal sample?

CS: Yes.

CV: We both do a lot of sampling as well, so listening to the upcoming release I was really struck by how contemporary and relevant it sounds. The technology hasn’t changed all that much.

CS: I think that the technology has changed and evolved in ways that makes a lot of things easier to do, but in those days with much more limited technology I needed to try to find creative solutions for what I was interested in doing. I’m glad that it still sounds fresh and new. The technology has evolved, but what I’m trying to do and say with my music has remained more or less the same.

CV: Have you ever had a chance to reach out to any of the artists who made the recordings that you’ve been using over the years?

CS: Yes. Not in every case, but in some cases I have. I wish I knew where I could find the little girl from Burundi, but that recording goes back to the 60s and she’s probably not a little girl anymore.

JAB: How recognizable is that sample? I’ve never heard the original, so I don’t know if it’s distorted beyond recognition.

CS: I don’t know. I like the ambiguity: it sounds vocal, but you can’t be 100% sure that it’s a vocal sample. It’s been through a lot, it’s been slowed down, looped, it’s been subjected to a certain amount of computer treatment. I’m not sure that if you heard the original you’d say “Oh, that’s it!”

CV: I feel like the beauty of sampling is that you get to put it through your own apparatus, with your own choices and particular aesthetics, and you become a filter of sorts. I love what we’ve heard from the catalogue. I’m wondering if you generate a lot of material and are really picky about what gets released, or if you work more minimally and deliberately.

CS: I have a lot of unreleased material that I’d like to get out there. I seem to have a certain psychological resistance to releasing my current work. When I release something, I know it gets fixed in people’s minds and memories, and I’m more comfortable doing that with music that’s 10 or 20 years old, which I’ve already moved beyond. For some reason—and I’m not sure it’s a really good reason—I’m less inclined to release the music that I’m working on right now, because I don’t want to fix it in people’s minds. I’d rather perform it live. On the other hand, I do sort of regret that people are maybe becoming more familiar with my older work and not really with my contemporary work, so I should probably put more effort towards releasing all of it.

JAB: “Mae Yao” & “Sonali” (featured on the new collection) are some of the first pieces of music you released, right? How does it feel to look back on those old compositions from where you are now?

CS: Chronologically, “Woo Lae Oak” is the first, from 1981. “Mae Yao” is from 1984, “Sonali” is from 1987, and “Banteay Srey” is from the beginning of the nineties. It’s been a nice experience for me to revisit these older recordings, contemplate how they fit in with what I am doing these days, and to be able to share them with an audience. I’m really grateful to Unseen Worlds for their continued support in releasing these tracks, along with their earlier release of my pieces from the seventies and eighties.

CV: Do you keep things archived and stored in categories or folders, so you remember what’s what?

CS: Well, first a piece will get a working title, which describes the process I was using or the sample I was using, or something like that. Eventually it will get titled using my silly system.

CV: We heard you use restaurants you like as titles.

CS: Yeah, I don’t really like coming up with titles that mean something or describe the piece or are any kind of poetic reference to the music, so I have a random system in which I pull titles from a list, and that serves as a way of identifying it. The list happens to be a list of restaurants that I enjoy. A lot of the restaurant names are in a language that’s foreign to me, so it moves the titles further away from meaning and description, and they become more abstract. “Banteay Srey” is the name of a Cambodian restaurant. I don’t even know what it means in Khmer.

JAB: (laughing) Do you go to a lot of restaurants? Are you an exploratory eater?

CS: I am an exploratory eater. I think that’s a better description than a “foodie.” I don’t really like the term “foodie” that much.

JAB: (laughing) Neither do I.

CS: I do eat out a lot, and I do like to eat new cuisines. I’m relatively fearless in terms of what I’ll eat. I recently went to an eel restaurant here in Tokyo and once of the things they serve was the actual bones, the spine of the eels deep fried and eaten like bar snacks.

CV: Was that restaurant added to your list?

CS: It hasn’t been yet, but it probably will be. The problem is that with my early pieces is that a lot of those restaurants have gone out of business or aren’t that good anymore. People will sometimes go to a restaurant that I named a piece after and say, “Hey, Carl, I went there and it was lousy.” But if the song is from ten years ago and the chef is gone…

JAB: All the same, I look forward to a Carl Stone song titles culinary tour. We played a few shows in Japan awhile back–one at a gallery in Kyoto and a few in Tokyo, including one in a temple. A good friend of ours helped us set it up–Chihei Hatakeyama.

CS: Oh, yeah. We’ve played a couple shows together. Where did you play in Tokyo?

JAB: We played at a Buddhist temple called Ennoji, and then we played at a small jazz club called Velvet Sun.

CS: Yeah, I’ve played there. With Chihei, actually!

JAB: We also did a show on Dommune Radio, which you’re probably familiar with. It was streaming live, and we met Ukawa.

CS: (laughing) Yeah, a character.

JAB: I read that you did a performance with Wolfgang Georgsdorf, and that he was playing a smeller organ.

CS: That’s right. He invented this keyboard that triggers aromas instead of notes. That kind of thing has been done before, and usually what happens is that you pump in a smell, and then another smell, and then another smell, and they all mix together until you end up with a big mess, but what’s interesting about his is that he worked with an aroma technologist and an engineer to work it out so that he could not only mix smells as he wanted but also replace smells with other smells. He has a great palate of aromas, and they’re not all nice smells like roses or honey. He had things like wet dogs, rotting leaves, sweat, horses, and mushrooms. He would mix them the way a painter would mix paints on a canvas, or the way a composer writing a symphony might orchestrate. It was really interesting to work together, first in his atelier out in the countryside and then in Berlin, where we presented in a church. The performance was about an hour long and the audience listened almost in the dark. I was using a lot of environmental sounds mixed in with electronic sounds. I think it was a really nice experience for the audience.

JAB: Did you prepare specific smell and sound combinations beforehand?

CS: Yes. We had a scenario worked out in advance, so there was a certain amount of improvisation, but he worked pretty specifically, at least with the flow of the smells. He asked me to keep that in mind for my musical accompaniment.

JAB: I love the idea of improvising with someone playing a smell organ, as if you’re a jazz trio but one of the band members is pumping in the smell of manure, and you react to that with sound.

CS: Yeah. Some of the smells he had were like wet earth.

CV & JAB: Aaaaaah.

CS: Because that has a smell, right? And the smell of cut wood. A lot of outdoor smells that we kind of take for granted as we pass them by.

JAB: Smell is such a strong trigger for memory…

CS: Very strong. I think it’s the strongest trigger, actually, more than sight or sound.

CV: It’s nice when it’s connected to a performance, so that particular memory comes shooting back if you happen across the smell. I was curious how often you find yourself recording. I’m sure it depends, but is it on a very regular basis? Do you have to be in a certain mood?

CS: A lot of times I’ll be working in my studio and then something interesting happens, so I’ll just fire the engines and start the recorder. Then sometimes I’ve allocated specific hours for recording, usually when I’m working with another artist. I’ve got various artists that I work with and we’ll block out times for recording sessions in the hopes of making a record. In terms of my own work, I usually don’t plan to record, unless I’m working on a very specific predetermined project, like a soundtrack. I’ll usually just be working, and then if it gets interesting I’ll record it. It’s kind of my process, to do it that way.

JAB: A lot of your earlier works are kind of very much process oriented—for example it’ll start with an idea that’s a sample, and then it’s the sample twice, and then multiplied by four, and then by eight. I’m curious how often you find that you’ll start with an idea like that and then follow through with it completely, versus having some flexibility for the process to shape the idea. Are you strict with sticking to the concept of a piece, or do you leave time to play with it while you’re developing it?

CS: That’s a very good question. Actually, it’s sort of both. Usually I start with what you could describe as a kind of play process, where I’m just playing around, maybe with a sample or with an idea for a process itself, and I don’t have any particular goal in mind. I’m just exploring what’s possible and having fun, and then at some point an idea will suggest itself—how to take this and shape it and make it into a finished composition, and where does it fit in with other material? Is this one sample or one process enough for an entire piece, or is it just one element of a larger piece? Who knows? The answers will emerge through the course of this play. I’ll try plugging in different samples and seeing what the results are. The only problem with this working method is when I’m on a deadline, maybe working on a film soundtrack where they give you a request for a certain emotional feeling and a certain duration. But because I don’t always know where I’m going to end up at the end of my process it’s hard to fulfill those kinds of requests–which is maybe why I don’t do many soundtracks.

JAB: Do you find the technology shapes the idea as you’re working with it? Or, another way of asking this might be, do you think your music is inherently tied to the technology that you’re using?

CS: That’s also a good question. I think the answer is that my work depends on technology to a great extent because I’m trying to work with things that aren’t in the realm of human performance, and aren’t necessarily possible for humans—I’m interested in things that are slower or faster or higher or lower or broader than is humanly possible to perform. In that sense I rely on technology to achieve those things. It’s not technology driven in the sense that when the technology changes or becomes obsolete, I go out of business—it just means that I adapt my process to whatever is available. So I don’t think the technology is driving me, so much as enabling me.

CV: Is there anything else you’d like to add, Carl?

CS: Hmm, you’ve asked some good questions. I hear that one of you is going to Belgium soon?

CV: Yeah, I live in Brussels. I go back and forth, but I’ve been there for about fourteen years. Are you going to be in Belgium?

CS: Yeah, I’m playing at a festival–not in Brussels, but in a small town. You know Meakusma Festival?

CV: Yeah–we’re playing! We’re playing two sets, one with our collaborative project (CV & JAB) and one as my solo project, where we’ll play synthesizers together with a string ensemble.

CS: That’s great! I have a unit called Realistic Monk with a Japanese sound artist who lives in Germany, Miki Yui–we’re playing September 9th. I’ll see you there! We have an album that’s coming out on Meakusma.

CV: Oh cool, they’re doing such great work. John played there last year so we can tell you it’s a wonderful festival. It’s in the countryside, but a lot of people come out from all over Europe. There’s a lot of good music. Well, it was really nice to speak with you, Carl–I really relate to a lot of your processes.

CS: I’m glad to hear that, and I’ll have to look into your music and hear what you guys are up to. Sounds like we have some mutual concerns!

———————————————

The Barbican Presents Yasuaki Shimizu & Carl Stone

———————————————