Guest post by Peter Harkawik

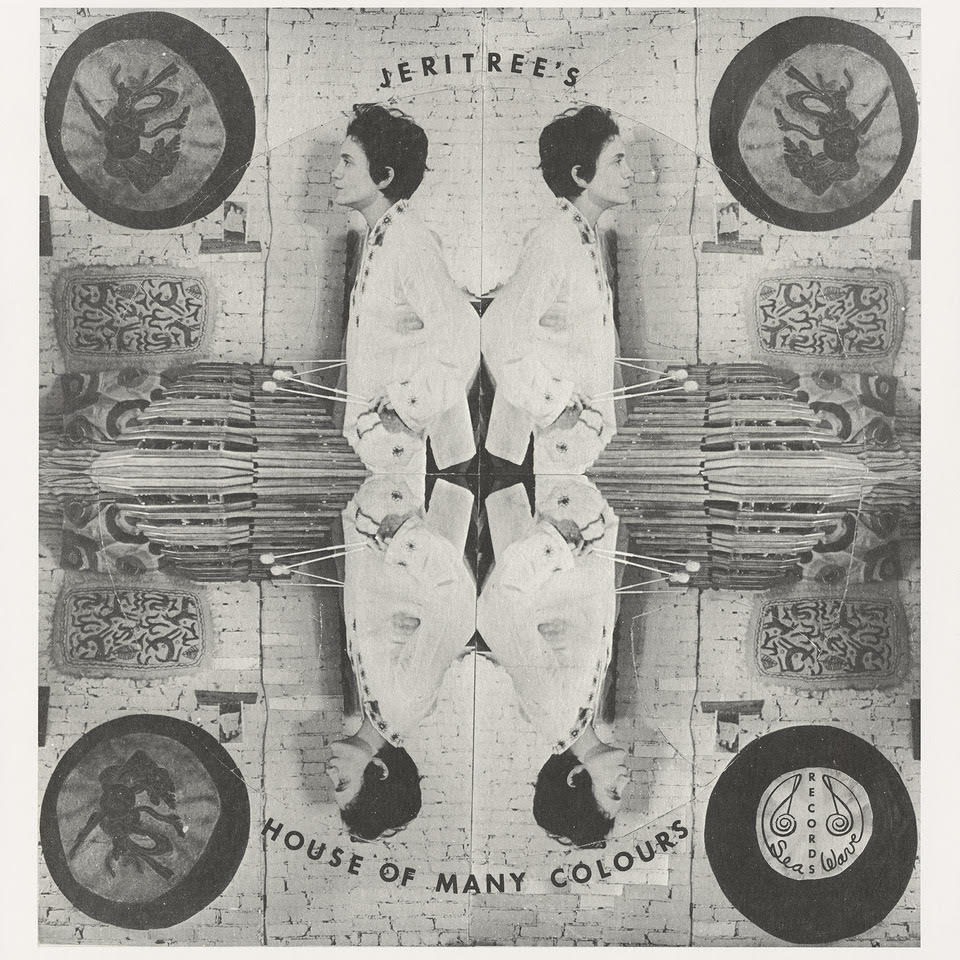

At a time when self-care is as much a multibillion dollar industry as it is a punchline, it seems wise to look back to a more substantial model for the articulation and maintenance of self. I’m confident that no better an example can be found than Jeriann Hilderley’s wonderful 1978 avant-folk record, Jeritree’s House of Many Colors. Jeritree is both persona and methodology, one that Hilderley inhabits and directs. Coming from a tradition of sculpture and instrument-building, she describes her work as “ritual dramatic music (creating conscious space that is healing, releasing and expressive), women’s music (diving deeply into my own womoon-self for the materials…) and creative music (creating a whole new world of meaning that comes out of the particularities of my existence).” Healing, specifically healing oneself through self-directed activity, is a central theme.

I haven’t found a lot of biographical information on Jeritree, save for the wooden yet enchantingly solipsistic jacket text. The LP was distributed by Kay Gardner‘s Wise Women Enterprises in Maine and lists a P.O. Box at Madison Square Station. 1978 was an extraordinarily generative time for the downtown music scene, which would soon give rise to New Music America, an annual nomadic festival showcasing New Music. House of Many Colors is a record equally at home with the Takoma stable as it as among members of this scene who experimented with vocals, such as Shelley Hirsch, Kirk Nurock, and Anna Homler.

“Sea Wave,” the nine minute opener, is buttressed by rolling, cacophonous cymbal crashes. To say that these evoke, symbolize or otherwise represent the ocean’s violent cycles would be entirely wrong. These thunderous crescendos are waves. They physicalize the music, inscribing the body of the listener and binding her to its rhythmic imperative. Hilderley’s vocals are shimmering specters that emerge from the stereo and linger in space long after the record has stopped spinning. Less about communicating or aligning the song with a particular style or expressive mode, they are a kind of personal evidence in the offing. The album’s title number (alternately, “Symphony of Little Sprouts”) is shortened from a 30 minute ritual performance piece and is described as a “meditational healing chant.” For me, the true delight here is the final piece, “Through Your Blue Veil,” a stirring devotional tune in which Hilderley somberly returns her lover’s assorted virtues, somewhat tarnished (“I give you back your perfect mouth/Less perfect since I have known you”). Its emotional power is shocking, disarming, and without comparison.

Hilderley’s vocals work against the marimba’s casual agreeability, and, as is the case with Robbie Basho, I imagine them to be the record’s polarizing aspect. While the instrumentation is an ode to the sonic and psychoacoustic possibilities of the marimba, her mournful warble has more in common with jazz and soul singers, taking her project out of the folk register. Billie Holiday, Nina Simone, and even Maya Angelou’s 1957 one-off Miss Calypso all come readily to mind. Hilderley worked closely with recording engineer Marilyn Ries to “milk” the marimba’s rich overtones, drawing on Japanese, Mexican, African and Central American traditions.

The power of House of Many Colors is in many ways demonstrative, and it more closely resembles a kind of praxis than a display of artistic talent or ambition. Its politics operate on a broad formal level, without slogans or entreaties to identify or exclude. I am reminded happily of the experiments of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, who by 1970 had given up plastic art for individualized psychotherapeutic encounters, or what she called “ritual without myth.” I can think of no better way to describe Hilderley’s stunning achievement.

This is incredible. Thank you

Thanks Peter! also Hi!

Truly amazing! Thank you!

Jen, just to greet you with a message (and contemplate said message for some time) is advantageous as an opening to a border of communication. Your merit as a curator is peerless. Reach out to me sometime, I’d love to converse about music/literature with someone who shares a similar appreciation for sound. -D.

Who holds the copyright to this song?

If you read this a reply would be much appreciated.