Guest post by Nick Zanca (Quiet Friend / Mister Lies)

I’m 20 years old, leaning against a window of a train from London to Edinburgh. The two other guys I’m traveling with, young producers with MacBooks and MIDI controllers in tow, are sprawled out in the seats across from me, eyes closed, dead to the world. At the start of that year, I had put out an LP (my first) of music I had felt unsure of, spent nearly every weekend of my sophomore spring semester in a different city, spun into a whirlwind, eventually dropping out of college to tour full time. Now it’s summer and I’m abroad and unready, unable to slow my racing mind. Instead, I retreat into my headphones, staring out at the passing Highlands in all their viridescence. In my ears sits a lone voice over a tranquil bed of strings, the ghostly hum of a vibrato circuit on a guitar amp lurking: “step right up / something’s happening here.” Sleeplessness becomes body high as the sun starts to rise.

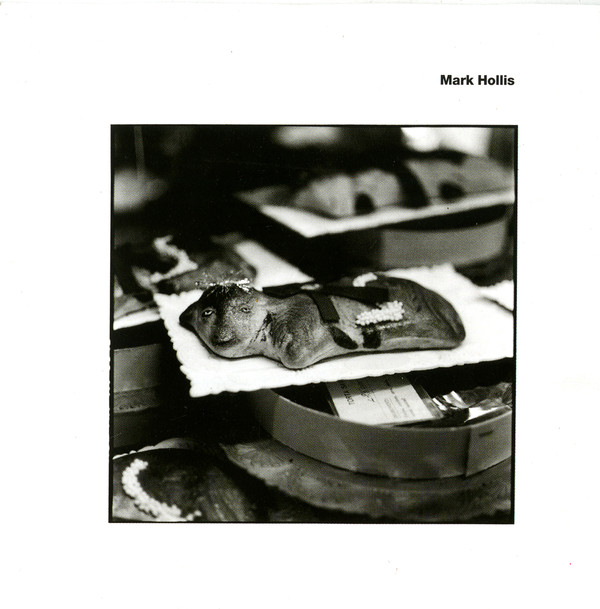

This is how I fell in love with Laughing Stock. That record, and later Spirit Of Eden, became instant companions through the months of endless travel and alienation that followed. The music of Mark Hollis would only hypnotize; it would help me process the change in direction of my life–a pointillist’s attention to detail, a fluidity I dreamt of possessing, a texture thick to the point of becoming a security blanket. Listening repeatedly, you feel as if you’re walking through an aviary of disparate songbirds, much like those depicted on the artwork, improvising in full awareness of their impermanence. In the midst of mental illness or writer’s block, I always use these records to recalibrate. To me, they’re sound of earth and sky meeting; above all, they taught me to embrace solitude through silence.

That silence is elevated even further on Mark Hollis, the solo record I arrived at later, quietly released seven years after Talk Talk disbanded. All electric instruments and studio magic are eschewed – instead, two microphones are placed at the front of the room, leaving the musicians in pursuit of their proper place in the stereo field as it was in the beginning of recorded sound. What we get, then, is that intimate, transcendental purity found in the films of Bresson or Tarkovsky or the music of Nick Drake or Morton Feldman–existing totally outside of time. Rather than utilizing chance and accident like the two preceding records, everything here was written down and scored–and somehow still, the music appears loosely structured, out of thin air, delicate as stained glass. Woodwind textures spurt, a harmonium breathes deep, cloistral voices whisper soft invocations. Often Mark’s voice will barely rise above the creaking of his chair or a ticking watch. You couldn’t find a quieter pop record if you tried.

In her essay The Aesthetics Of Silence, Susan Sontag describes art as “a deliverance, an exercise in asceticism.” She says:

…Formerly, the artist’s good was mastery of and fulfillment in his art. Now, it’s suggested that the highest good for the artist is to reach that point where those goals of excellence become insignificant to him, emotionally and ethically, and he is more satisfied by being silent than by finding a voice in art.

Of course, the relationship Mark Hollis had to silence was never limited to sound–he withdrew completely from the public eye to focus on his family shortly after this record was released. He would claim that the work behind him was so close to how he imagined music that he couldn’t possibly dream of how to move forward from it. Many of us held out for one more record, one more sign of life. It would never come, and even as heartbroken as I am now that he’s gone, to ask for more would be selfish. One listens to these records at least once a week and still learns from them.

A little over twenty years later, the music industry has eaten itself. As a discovery platform, streaming services reduce even the most unorthodox music down to exclusive, rudimentary listening contexts– dinner parties, “mood boosters,” “lo-fi beats to study to”–as if it wasn’t bad enough that they barely compensate. Young artists online hardly thrive, if ever, on transparency and instant validation–to keep your work close to the chest is somehow to become estranged; we assume the role of “wearing” our music beyond simply letting it sing for itself. At the time of writing this, I’m holed up finishing a project that I struggle with keeping a secret. I’m sometimes so swept up in considering how and where it’ll be placed–contexts that I can’t control, try as I might–that I forget to be honest with myself. I listen to the work my hero left behind and I hear a vision of sound uncompromised, a commitment to the organic, an atmospheric intuition, and those troubles are kept at bay. I’m forever indebted to the standard Mark Hollis set and am inspired to stay true to all of the grey areas. I only hope the people introduced to his work for the first time this week will stumble upon a similar solace.

If this is your first listen, wait for a quiet moment to press play. In his words, “You should never listen to music as background music.”

❤️

thank you

R.I.P. Mark Hollis.

Thanks. It’s rarely mentioned but Hollis is a huge influence on Kevin Shields.