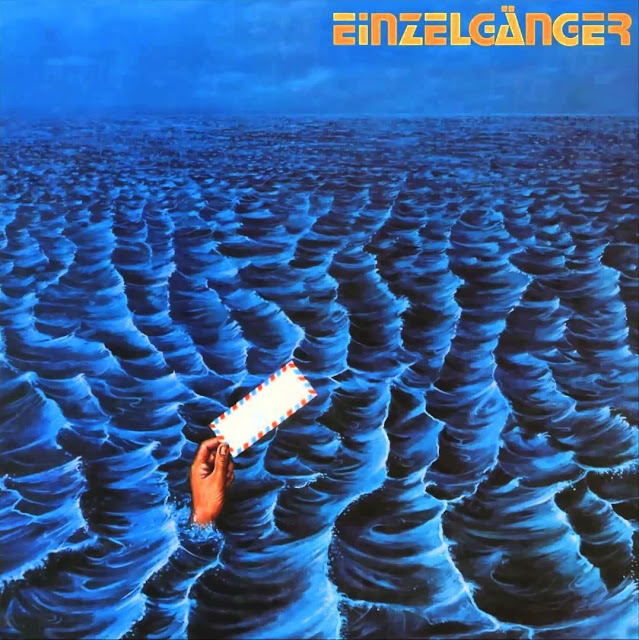

Einzelgänger – Einzelgänger, 1975

Aura was the last album from jùjú music pillar King Sunny Adé before he left Island Records, purportedly because of increasing pressure to westernize his sound. You can hear it, too–Aura is much beefier than his other two Island releases, the classics Juju Music and Synchro System. It’s plumped up and pulsing with drum machines, electro beats, and synth samples–arguably not a bad thing. King Sunny Adé was the first to introduce the pedal steel guitar to Nigerian pop music, and it shines here on top of a dense flurry of percussion, thanks to six percussionists and plenty of talking drum. Featuring a Stevie Wonder harmonica solo on “Ase,” and Tony Allen on drums in “Oremi,” this is not traditional jùjú music, but the endlessly rolling, meditative grooves and the joy are still there in full force. A perfect summer record. Thanks for playing this for me in your car, Kat!

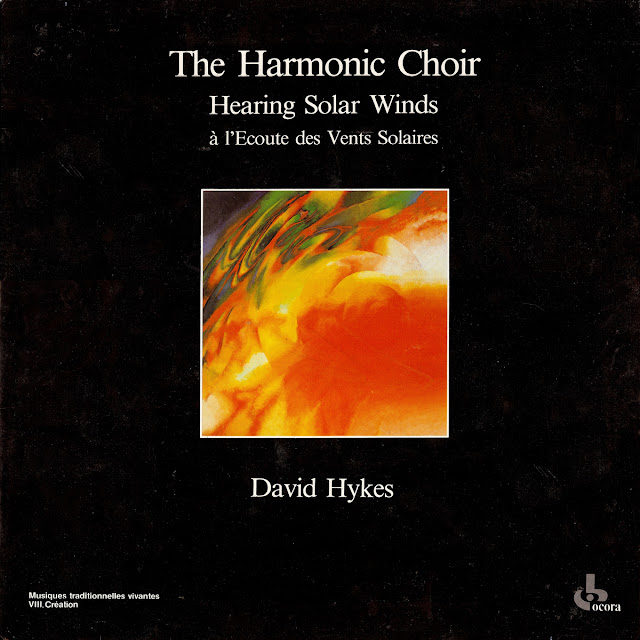

“This recording was made in L’Abbaye du Thoronet, a 12th-century Cisterian monastery in Provence, where I had previously brought the choir in 1978. The simple harmonic geometry of the abbey seemed perfectly proportioned to magnify the choir’s music and let it resonate within its sacred space. Working there was an incredible challenge: our sensations, our breathing, and even our thoughts and emotions became intensely amplified.”

–David Hykes, liner notes

When I played the album for Joe Smith, the president of the label, there was a stunned silence. Joe looked up and said, “Song Cycle”? I said, “Yes,” and he said, “So, where are the songs?” And I knew that was the beginning of the end.