Guest post by Michael McGregor

Hitomi “Penny” Tohyama is a Japanese singer who had a string of hit records in the late ’70s and ’80s. The earlier stuff is disco-funk in the J-Pop style, with YMO/Tatsuro Yamashita influences — smooth, electro production, with great synth bass-lines, and superb melodies. Some of her stuff in the late ’80s gets pretty cheesy, but Sexy Robot is a gem from front to back.

I can’t remember how I came across it — probably in a Hosono YouTube K-Hole — but my ex-girlfriend and I used to jam this record every night while making dinner — dancing around the kitchen, pouring more wine, turning up the volume. It’s catchy, despite 90% of the lyrics being in Japanese, though every few bars she’ll drop a phrase in English — something as short as just bursting out “Sexy robot,” or some groovier vocal progressions like “Sparkling eyes…fall in love…I am so sexy.” It’s one of those records that makes you feel sexy inside, and fun(!). Even if you listen to pretentious ambient or noise or techno all the time, this one is undeniable. It’s a reminder that despite all the awful things going on in the world, life is pretty great.

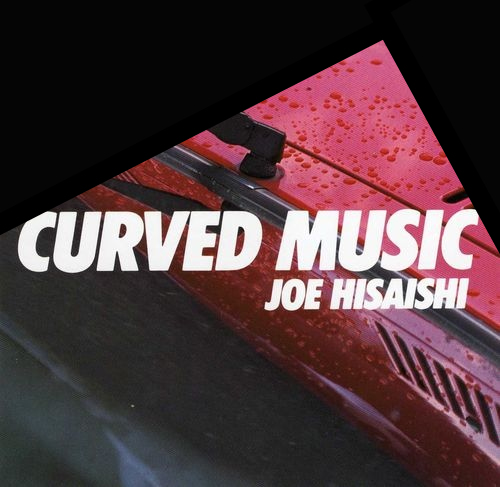

To sum it up — when you title your record Sexy Robot and have a cover like this, it’s hard to go wrong.

download