Hildegard von Bingen – A Feather on the Breath of God, 1984

Guest post by Cora Walters

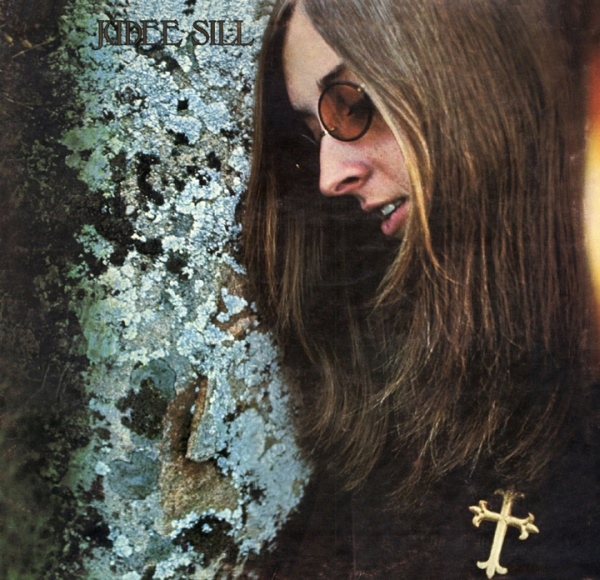

The more I listen to Judee Sill’s music, and specifically this album, the more I come to think of it as a church. The perfect soundtrack for finding your way. Her earnestness and skill as a singer and lyricist certainly rank her among the sweet sirens of the seventies–Joni Mitchell, Vashti Bunyan, Karen Dalton, Linda Perhacs, Bridget St. John, Nico–but what sets her apart is her constant craving. Surreal parables swirl around, clutching to make contact or to make sense of the world and her place in it. Each song is a hymn of her own mystical making. Even at its most baroque (“The Archetypal Man”), twangy (“Ridge Rider”), or pop (“Jesus Was a Cross Maker”), she’s driftin’ and “lopin’ along” some serious terrain–the rocky road to salvation.

Mariah was the brainchild of saxophonist Yasuaki Shimizu, who is most well-known for his solo performances of Bach’s cello suites in acoustically interesting spaces (he recorded in a mine, he did some work with Ryuichi Sakamoto, we love him, etc.). His work with Mariah was a far cry from the rest of his career, though–Utakata No Hibi, the band’s fifth and final LP, is loosely woven, big and wide open and facing skyward. The album is built around percussion, which ranges from traditional Japanese to tribal to Talking Heads-y, pencilled in with simple synth textures and spikes of brass. The songs are mantric, with vocals in both Armenian and Japanese that act more as an instrument than as a focal narrative. The definitive high is “心臓の扉” (“Shinzō No Tobira/Door of the Heart”). No filler, though–all the less poppy moments are a joy, and manage to simultaneously feel futuristic and medieval.

Maria gave me this record years ago, and it’s been in heavy rotation ever since. We’re really excited that it’s being reissued on Palto Flats, a label run by personal DJ hero Jacob Gorchov. It’s an important record that speaks to a wide range of people, and the attention it’s attracting is well-deserved. The New York release party is tonight, with vinyl for sale. Sample the remasters below, or listen to “Shinzō No Tobira” in its entirety here.