Guest post by grandiose melodrama connoisseur René Kladzyk (Ziemba)

“The stars are not so silent

As they seem

They sparkle for you

You’re gazing at me

Knowing that up till now

I never believed in love”Songs in the air

Everywhere

Telling me up ‘til now

I never believed in love”

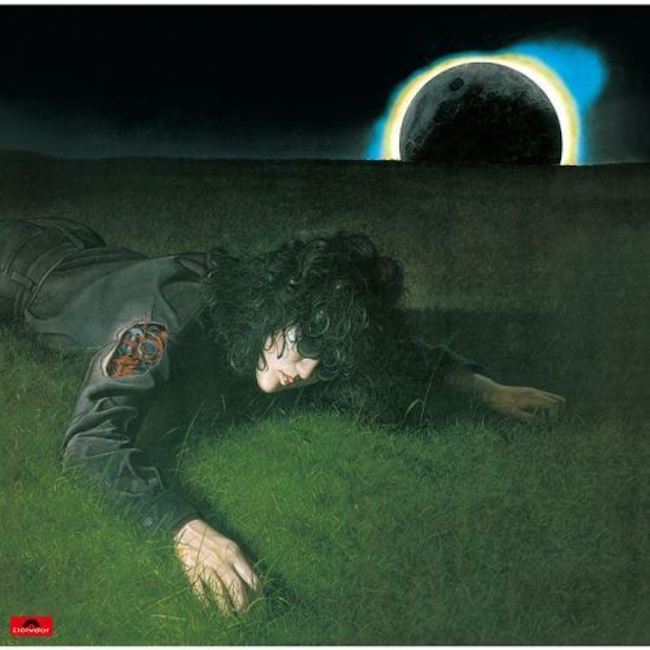

Annie Haslam’s voice is a ringing bell at the center of Annie in Wonderland, a 1977 maximalist pop adventure created in partnership with Haslam’s then-fiancé Roy Wood (better known as a founding member of Electric Light Orchestra, The Move, and the terrifying frontman of Wizzard). Haslam’s first solo album Annie in Wonderland was a major sonic departure from Renaissance, the avant-baroque progressive rock band fronted by Haslam. While the songs of Renaissance also orbited around the soaring purity of Haslam’s voice, it’s with Annie in Wonderland that Haslam’s expression became overtly romantic, igniting this sweeping and grandiose pop melodrama of an album.

At times choral, at times outright bizarre and sweetly silly, Annie in Wonderland oozes with a sense of wonder and a playful mysticism. The nostalgic excitement of love is also omnipresent, and the fun had while making it eminently apparent. In a 1999 interview, Haslam comments that this is her favorite of her solo albums, and that recording sessions would frequently get held up by riotous laughter, with everyone on the floor crying laughing.

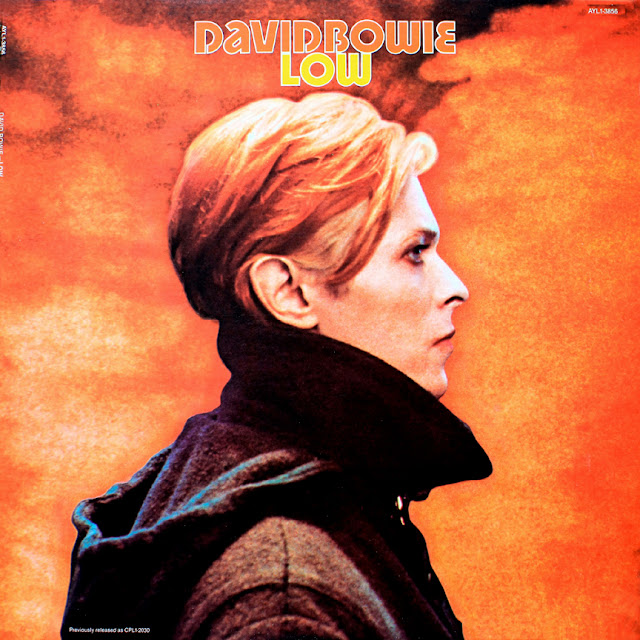

A loungey cover of “Nature Boy” reapproaches the standard with a cinematic mystery; I’m eagerly awaiting the femme James Bond reboot featuring this song as our heroine drives along the ragged cliffs of the Italian Riviera. Meanwhile the excellent “I Never Believed in Love” draws clear throughlines to more disco-inflected and glammy songs in Electric Light Orchestra’s catalogue, like the Xanadu soundtrack that would come out a couple years later. Of course Roy Wood’s influence can be heard abundantly throughout the record, as he produced, arranged, played the majority of the instruments. He also did the album art, which includes several hints at specific references to the recording process.

The romance and divine sensibility of Annie in Wonderland carries through in Annie Haslam’s later solo work, especially in standouts like “The Angels Cry” from her 1989 self titled album, and can be spotted in Haslam’s visual art as well. Her current website features intuitive paintings of songs, custom painted musical instruments, garments, and pet portraits, all cast in vibrant and multicolored hues evoking sensuous dream worlds.