|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

Tag: 1990

Hoedh – Hymnvs, 1990

Peak dark ambient. The first of two solo records from German trance and ambient musician Thorn Hoedh, who passed away in 2003. Equally lauded as a holy grail of the genre and bemoaned as an overlooked masterpiece, Hymnvs manages to be both sprawling and claustrophobic; cinematic and lo-fi; inorganic and classical. If you’re not paying attention, these seven long-form tracks (or hymns) might appear like a flat and unchanging expanse of black tones, but a few seconds in headphones proves otherwise–there’s actually a great deal of intricate movement happening beneath the surface, so much so that tracks like “Das Geistige Universum” seem to actually evoke the nausea of being pitched around in a boat in choppy water. Elsewhere, ringing overtones and expansive, bending pitches, as on “Hoedh (Sonnenklang)” are completely sonically disorienting. There is, in short, a lot going on here.

I love the anonymity of the instrumentation–it’s frequently unclear whether we’re listening to an acoustic instrument that’s been modified, or to a synthetic interpretation of an instrument. Still, the sounds are warped around the edges in familiar ways: “Heilige (Mantra Der Rotation)” has the gape of wind instruments in a massive tunnel; other tracks feature synthetic remnants of strings, piano, horns; but always we feel a certain kind of crackling closeness that can’t simply be attributed to lo-fi production (though there is a distinct feeling of of well-worn vinyl). It’s as if the sounds have had tiny shading details painted onto them by very meticulous hands.

It seems as if listeners have consistently ascribed a deep and impenetrable melancholy to Hymnvs, and it’s true that it imparts a feeling of descent, or even of disassociation. But if listening to this record is the sensation of slowly sinking backwards into water while looking up at the receding surface, then inevitably there are beams of light penetrating the surface, sun-dappled and speckled with dust motes, which is to say that Hymnvs is flecked with joy, with optimism, as the best hymns are. For fans of The Caretaker, Gavin Bryars, William Basinski, or, uh, Wagner.

Per Tjernberg – They Call Me, 1990

An ambitious and highly effective combustion of ambient jazz and a slew of musical traditions, whirlwinded together with dizzying, almost violent enthusiasm by Swedish jazz percussionist Per Tjernberg. Gamelan textures, Indian tabla, Aboriginal didgeridoo, Gabonese and Cameroonian sanza and mbira humming, Japanese strings, African flute, oud, and drums from too many countries to name.

While writing this post I realized that Tjernberg is also responsible for this reggae-pop treat (released under the wink-wink pseudonym Per Cussion) that I’ve had in my “tracks to do things with” pile for years. That he succeeds at such wildly different efforts (which are equally unabashed in their proclivity towards cultural borrowing, or, you know, appropriation; call it what you will) is a testament not just to his musicianship (though They Call Me is his first release under his own name, he was already well-seasoned in other projects) but to the grace with which he applies textures outside of their traditional contexts and shapes them into landscapes that sound simultaneously very terrestrial and slightly alien. (Relatedly, he’s also touted as the first Swede to make a rap record, which he did with the aid of American rappers, and about which I have nothing to say other than that I like the kalimba.)

There is, as you might expect, a lot going on here, but They Call Me shifts comfortably between wild freeform jazz and more subdued textural motifs, and I (predictably) think its strongest moments are when it leans into the latter mode. The title track, as well as “Didn’t You Know…Didn’t You Know” (previewed below) are very high highs. The closing track, “This Earth: Prayer,” is stunning in scope, managing to do so much with what is, for much of the song, just a didgeridoo, a lone brass instrument, and some light percussion. It evokes whales and also something even more cosmic, and I’m reminded strongly of Deep Listening every time I hear it. I don’t know that this record is for everyone, but if it’s for you, it’s definitely for you.

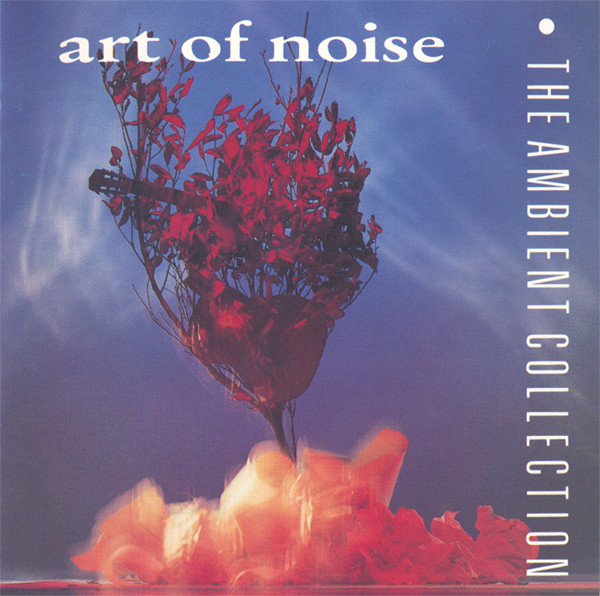

The Art of Noise – The Ambient Collection, 1990

One final send-off to a perfectly nightmarish year. This technically isn’t an album but rather a compilation, mostly of tracks from The Art Of Noise’s 1986 In Visible Silence and 1987 In No Sense? Nonsense (both of which, if you’re unfamiliar with the group, are incredibly generous places to start). This collection was compiled by regular AON collaborator Martin Glover (aka Youth, a member of The Orb) with some tasteful mixing and transitions by regular Alex Paterson, also of The Orb.

This isn’t exactly what we think of as ambient these days, but boy oh boy is it a prime early 90s time capsule. If you’re an Art of Noise fan, you’ll love hearing favorites like “Crusoe” and “Ode to Don Jose” in slightly more vivid hi-fi. Try not to be put off by the language excerpted below–these are brilliant songs, and they make a lot of sense tweaked into an explicitly balearic context, given that a lot of AON signature synth textures and environments feel like very direct precursors to what is described below as ambient house. Includes “A Nation Rejects” and its successor “Roundabout 727,” the riff from which has famously been sampled in too many rap tracks to count. Choral samples, ocean waves, hypnagogic percussion, and cotton candy synthesizers. It’s almost embarrassing how up my alley this is, so I hope it’s the same for you.

Enjoy, thanks for reading, happy new year, and may we all be on the up and up.

With the advent of the nineties a new decade of clubs and DJs have floated into our consciousness. Their trip is a journey into peace. An ambient ecstasy. The creation of a new musical travelogue. A minimalistic embrace of everything good about the hard and uncompromising trance-dance of house and the surrealism of ambient instrumentalism.

Ambient or ‘chill out’ rooms have been set up in clubs all around the country as an alternative to the dance floor. Pure ecstasy escapism. Rooms for day-dreaming, fantasising or hallucinating.

This ambient collection is a sound step into the future. A collection of tracks alternatively known as ‘New Age House’ or ‘Ambient House.’ Everyday sounds, noises and atmospheres we’ve imagined and heard all our lives but never consciously listened to. An unfocused daydream with no background or foreground. A sense of not being yourself, or being apart from what you’re listening to. A draft into tranquility, in and out of reality.

Oft played and more than often sampled, The Art Of Noise have long been torchbearers for this form of ambient instrumentalism. So…chill out.

Andreolina – An Island In The Moon, 1990

Sublime collaboration between Silvio Linardi (who’s collaborated with David Sylvian, Hector Zazou, Roger Eno, and others) and Pier Luigi Andreoni (whom you may know from The Doubling Riders). Ricardo Sinigaglia makes a few appearances too, first on piano and then on an Akai S 900. This was their only release as Andreolina.

Sprawling, weightless instrumentals that never stay soporific for too long. You can hear Andreoni’s classical training in much of this, and not just because of how much oboe there is, but structurally too. The name of the album comes from an unfinished piece of William Blake prose, and some of the song titles are Blake references as well–so while it might be power of suggestion, there seem to be tinges of romanticism dotted throughout, whereas other moments veer off into jazz. Lots to love here for Elicoide fans.

As an aside, this was released on ADN, the same label responsible for Tasaday’s L’Eterna Risata and the aforementioned Sinigaglia record. Depending on who you ask, ADN can stand for A Dull Note, L’amore del Nipote, or Agnostic Dumplings Nursery.

Gavin Bryars – The Sinking of the Titanic, 1990

Bride did not hear the band stop playing and it would appear that the musicians continued to play even as the water enveloped them. My initial speculations centred, therefore, on what happens to music as it is played in water. On a purely physical level, of course, it simply stops since the strings would fail to produce much of a sound (it was a string sextet that played at the end, since the two pianists with the band had no instruments available on the Boat Deck). On a poetic level, however, the music, once generated in water, would continue to reverberate for long periods of time in the more sound-efficient medium of water and the music would descend with the ship to the ocean bed and remain there, repeating over and over until the ship returns to the surface and the sounds re-emerge. The rediscovery of the ship by Taurus International at 1.04 on September 1st 1985 renders this a possibility. This hymn tune forms a base over which other material is superimposed. This includes fragments of interviews with survivors, sequences of Morse signals played on woodblocks, other arrangements of the hymn, other possible tunes for the hymn on other instruments, references to the different bagpipe players on the ship (one Irish, one Scottish), miscellaneous sound effects relating to descriptions given by survivors of the sound of the iceberg’s impact, and so on.

Prefab Sprout – Jordan: The Comeback, 1990

N.A.D. – Dawn of a New Age, 1990