Todd Barton is an accomplished composer and musician whose lifelong investigation into sound has taken many forms. He has built Renaissance musical instruments, lectured on the musical notation of the Middle Ages, and written numerous scores for the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, where he was Resident Composer for over 40 years. His DNA-derived Genome Music has been the subject of numerous articles and exhibitions, and he has released several albums of Zen Shakuhachi meditation music. Since 1979, he has been composing and performing works for analog synthesizer, and is currently a consulting artist for Buchla USA. He’s a generous and dedicated educator, and in recent years has contributed a wealth of knowledge about Buchla, Serge, Hordijk and Haken synthesizers to various online platforms. Among his discoveries is the Krell Patch, named for the self-generating circuits that Bebe and Louis Barron created for the 1956 film Forbidden Planet. In the early 80s, Barton began a collaboration with author Ursula K. Le Guin that became the recently reissued Music and Poetry of the Kesh, a “speculative music” for the fictional peoples of the 1985 novel Always Coming Home. In addition to Le Guin, Barton’s collaborators include Anthony Braxton, Zakir Hussein, William Stafford, and Lawson Fusao Inada, and his compositions have been performed by the KRONOS Quartet, Oregon Symphony Orchestra, San Jose Chamber Orchestra, and the Shasta Taiko, among others.

Interview by Peter Harkawik, a Los Angeles based artist working in sculpture and photography.

———————————————

Hi Todd, thanks for being here! To start, where are you, and what are you working on these days?

Hi! I’m in my studio in Oregon. I have a solo Buchla Easel performance coming up at Modular 8 in Portland on June 10, and I’ll be performing at The Tank in Colorado in the Fall. I just finished a composition for Tone Science Module 2, and now I’m working on a collaboration with UK painter Edward Ball. The rest of my time is spent teaching modular synthesis and exploring sound in the studio.

Can you tell me a little bit about your process for making an album like Music from the Studio? I get the sense that it was culled from a larger assortment of recordings.

Good intuition! I actually made it years ago for immediate friends and family, including my grandkids. They had heard my work through the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and when I’d play them the more serious, more abstract electronic work, they’d nod and say, “Yeah, that’s cool.” (laughs) I wanted to make something more accessible for them. It’s all the Music Easel or Buchla 100 or 200 series, and there might be one on there that’s made with the Haken Continuum.

How does the specific cultural history of the Buchla factor into your work? I’m thinking of the Tape Music Center, Experiments in Art and Technology, and the ethos of the 1960’s. Is it kind of baked into the instrument?

Absolutely. Don Buchla created the 100 system for Morton Subotnick at the Tape Music Center. His approach to synthesis, which was so different from Moog on the East coast, is immediately evident to anyone who has ever touched a Buchla instrument. One of my favorite quotes from David Tudor is something like, “I don’t try to make the synthesizer do what I want it to do, I listen to what it wants to tell me.” If you listen to a Buchla, it will start rewiring your synapses.

How has making electronic music changed since you first started working with synthesizers?

The person who turned me onto the Buchla back in the 70s was a guy named Douglas Leedy. His major album is Entropical Paradise which was done on a Buchla. He popped in and out of Tape Music Center, so there’s one degree of separation there. I bought my first synth from Serge Tcherepnin in Haight-Ashbury in 1979. For the first 10 years it was a Serge and a Roland Jupiter-8. By 1985, the Yamaha DX7 and the Korg M1 had come out, and everyone went digital. Sure, Stockhausen, Subotnick, lots of folks had taken the analogue synthesizer to great heights, but I felt there was more to learn. I was raising my hand and saying, “Wait! We haven’t found the edge of analog synthesis yet!” People looked at me like I was the village idiot. They took pity on me and gave me their analog gear, and by the mid-80’s, I had a wonderful collection to experiment with. Now we’ve come full circle and everyone’s getting back into analog. Eurorack is taking off. Morton Subotnick is having a great second act, touring all over the world with both older and newer work. People are starting to push the analog envelope further, and doing it through the lens of all the genres of music that have cropped up since 1980—hip hop, dub, trance, etc.

As a new generation of musicians discover the Buchla, what do you see as your role?

Don Buchla created a musical instrument that he said had no “preconceived ideas.” He wanted people to figure out how they wanted to interface with it. You see that with Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith, Alessandro Cortini—they’re bringing their own voice to the palette. For my part, I’m obsessed with sound, with the “Buchla Paradigm.” Every day I explore with sound in the studio. Since I retired from the Shakespeare Festival, I’ve been making little videos, putting them online, sharing my discoveries and hoping people take them to places I never considered.

A friend of mine told me that her first boombox came with a CD of music by Paul Lansky, as a demonstration of the burgeoning potential of the CD format. I thought that was funny at the time, but now it strikes me that all electronic music is in a sense a kind of demonstration. How do you draw the line between the music you make, say, for the purpose of showing off the capabilities of the Buchla, to what is considered a song?

Well, for me, demos are demos. If I’m exploring sound, I’ll stumble onto something with one of these synthesizers, be it a Serge, a Buchla or a Hordijk, and I’ll think, “Oh that’s interesting,” and I’ll make a demo of it. Sometimes I’ll do a voiceover and say, “Here, let’s patch this together,” or, “Here’s what it does, these are the knobs you want to explore first, but feel free to take it further.” Sometimes the demo will just be the camera on my hands on the synthesizer, but I’m still exploring some specific aspect, and each aspect becomes another arrow in my compositional quiver. The word compose is Latin for “to put together.” When I compose, there’s definitely intent there. Sometimes the structure presents itself as you’re sculpting the sounds. I might say, “Well, what if I start here, and then go towards this.” I might change a few things on the way there, but the process creates the form.

I grew up performing acoustic music and composing for string quartets, small ensembles, and orchestras. Everything was written out. When I’d write a note, it would tell a musician what fingers to put down on their instrument, how loud to play it, etc. But when I started composing electronic music, I was composing from the perspective of the sound, not the musician. I was creating a sound that wasn’t, say, an oboe, or a clarinet. It might have some sonic gesture, some glitch or grit in it that’s not even possible on an acoustic instrument. Composing electronic music is a completely different ballgame because you’re creating at a granular level, making up the instruments as you go. A composer can use the twelve-tone system in a serial way or in a more harmonic, melodic, modular way, but it’s still just 12 notes. A synthesizer can get everything in-between, all the bizarre timbres and tone colors of your imagination.

This touches on something I saw recently in a documentary about Canadian composer Martin Bartlett. He spoke about the potential for electronic music to erase the distinction between composer and performer, presumably because the composition process can be done by way of patching in real time. Is this how you think about performing with a synthesizer—“composing” for an audience?

Absolutely. It goes all the way back to Stockhausen, the idea that a musician can actually “hold” sound, create sound from nothing. I create compositions that end up on CDs, cassettes, or LPs, and often the bulk of that comes from improvisation, and I might layer it, remix it, tweak it a lot. Other times, when I do a performance, let’s say for 30 minutes, I feel that I’m performing a composition, even though it is completely free improvisation. The Buchla Music Easel has all these beautiful colored sliders, switches, knobs. Sometimes before I start I’ll have a ten year old come up from the audience and move everything around. Then I turn the volume knob up, and start from there. I follow that sound to a composition, to an improvisation.

You did a project in 1997 where you composed a roughly one minute piece every day for a month, then released it to CD and the web. In the liner notes, you encourage the listener to “reprogram” the CD by listening out of sequence. Is this kind of interactive listening something you’ve explored further?

I don’t know that I’ve explored that since. This was the 90’s, so the idea was kind of ”make your own playlist.” In a way, it was an excuse to use every synthesizer in my studio, even the neglected ones. I woke up every morning and I had until 10 o’clock to finish the piece, and then I would put it online. For each synth, I had to re-learn or re-figure out what it was telling me, and go with it.

My first experience with electronic music was probably in the late 90s, early 2000’s. I remember going to noise shows, where the setup was almost always a solitary person on the floor surrounded by electronics that were being fiddled with. Do you think electronic music is prone to this kind of relationship, where a performer is in a sense in dialogue with themselves or their own “feedback loop,” or can it be more of a social process?

I think it depends a lot on the venue. I do Easel duets regularly with my colleague, Bruce Bayard. A few years ago, I got four performers together. That was a bit of an homage to the Electric Weasel Ensemble, which was Don Buchla, Allen Strange, Pat Strange, Steve Ruppenthal, and David Morse. Those five were actually the first to get Easels. When I was in Berlin in October I did a little talk and a solo set, and then afterwards there was a jam with six other synthesists. Almost every city now has a synth meet. LA has Modular on the Spot. I think they meet in those big drainage ditches that don’t have water in them.

We call that “the river.”

Yes! I hear they play at different outdoor spots all over LA. They’re mostly solo artists, but they have a community. I think the solo paradigm is equally valid. I’ve been plenty of places where there’s just one person on the floor surrounded by DIY stuff, foot pedals, doing their thing.

I’ve been reading about Terry Riley’s 1958 improvisations with Pauline Oliveros, about how the rule was that they wouldn’t speak before or during the session, only after. It’s interesting because my first exposure to minimalist music was in the context of these very tight, very contained performances and recordings. As I learn more, I’m finding out about the social history, connections to Stuart Brand, things like the Homebrew Computer Club, that history of California experimentation. These were also jam sessions.

You know, Don Buchla created speaker arrays and mixers for the Grateful Dead, for processing their sound.

Wow, really?

Yeah. And the other person doing that was John Meyer. His speakers are the gold standard these days. He was working with Don.

Do you think about the aesthetic experience a musician has with an instrument, especially one like the Music Easel or the Continuum? I don’t mean the look of performing with it, but the personal experience of the musician.

I think about timbre and wanting to, what I’d call, “follow the sound.” If I’m doing an improvisation or I’m composing notes on paper, there’s a continual feedback to the sounds that are happening. I try to guide or sculpt the sound into something new, or at least new to me, and the feedback keeps going. Sometimes I try to sculpt it in one way, and it goes in another, and I think, “Oh, that’s interesting.” I come from a wind instrument background. I grew up playing trumpet, and I’ve studied shakuhachi for 30 years now. The gestures I make, have made my whole life, are connected to breath. If you really practice, you can hold long notes on the trumpet, but eventually the breath runs out. The oscillator on the Easel will keep going as long as there’s electricity. I just finished a piece that I sent off to the UK for a compilation. It’s full of long, washy, drone sounds, with harmonic timbres that go from very consonant or thin, to very dense and complex. Those shifts are probably not unlike a slow breath.

I’m noticing, especially on an album like Analog Horizonings, the influence of Indian classical music.

I was exposed a lot as a teenager to Indian music, ragas, and I personally played tamboor in some sessions, so it’s an influence for sure. I’ve done some meditation music too. My friend who plays sitar, Russ Appleyard, studied and toured in India for years. He and I also at one point in our development locked into didgeridoos. There were a few years there where that was just it. There were stories about aboriginal cultures that would play didgeridoo from sunset to sunrise. I remember we got about three hours once. It was mind-altering.

I’ve been listening to an excerpt of your extraordinarily beautiful tape from 1986 called I/Shi-Ho: Meditation Environments. Can you talk a little bit about this piece? Are all the sounds on this tape made with a synthesizer or are there vocal samples as well?

I think I was influenced a little bit by Brian Eno’s Music for Airports and things like that. I didn’t have much technology at that point. The samples are actually (laughs) either an 8-bit Ensoniq Mirage, or maybe a Korg Wavestation. Pretty primitive compared to today. Maybe a Roland Jupiter-8 made it on there for a drone or washy thing. I was probably using the first iteration of a software DAW called Cakewalk. Version 1! The title came from the I Ching.

I don’t know anything about making music, but I have accidentally built some sculptures that turned out to be musical. It strikes me that there’s a great many reasons to make your own musical instrument: achieving a different sound, actualizing a kind of philosophy or worldview, producing visual spectacle, or just for ergonomic reasons. Can you talk about the instruments that were made for Music and Poetry of the Kesh?

When it comes to instrument building, I was more of a dabbler. I made baroque flutes and trumpet mutes–that’s really a niche there–and renaissance recorders. That informed a part I wrote in Music and Poetry of the Kesh where I described Kesh instruments. Ursula Le Guin and I would bring instruments that we had “found,” in our imagination, from the Kesh culture. I would describe them, and explain how they were built and what sounds they made. Of course, as she was working on the book, I was working on the music–this was from 1983 to 1985. We didn’t have time to build these instruments and beta test them, so I did it all on a Roland Jupiter 8. Once the book was published, people actually started building these instruments, and they ended up sounding like what I had dreamed they would sound like! Since then, I haven’t built any instruments per se, but anything can become an instrument—found metal, found wood. These days, in the electronic world, it’s people with their Arduinos and Raspberry Pis. That’s beyond me.

Really?

I don’t have a lot of technical experience in that way. I know what a resistor and a capacitor do, but I couldn’t build anything from scratch. I’m a composer and performer fascinated with sound. I have a working knowledge, and I’ve soldered up synthesizer modules, but that doesn’t mean I know exactly what that resistor’s doing when I put it in there. People will cold call or email me with two pages of “Is that plus or minus five volts?” I read it all, and say “I’m sorry! Please contact my friend so-and-so.”

You’ve said you’re not interested in producing a traditional score where the timbre would be open to interpretation, but if that’s the case, how do you notate your music? Is there some other format or way of making a score that interests you?

Well, there are formats out there. I’m not categorically against scores for electronic music—

(The interview is interrupted because Barton finds a black widow spider.)

Those are serious. I was bitten once, it was horrible. I had a fever for a month.

I think I got it. Where were we? Oh, scores. A score for electronic music, and I’m being totally reductive here, is a graphic score. A score might say, “Start with this curvilinear gesture, play it for 30 seconds, then that’s followed by this series of plots,” etc. There’s a huge history of that from the 60s on, with some really amazing scores out there, but it presupposes you’ve got musicians who have worked in an improvisational way and are open, imaginative, and creative about how to interpret it. Sarah Belle Reid, who teaches at CalArts, started a score project called The Postcard Project (which was inspired, in part, by James Tenney’s Postal Pieces). She sent me a postcard of a graphic score, and I then interpreted it using the Music Easel and sent it back to her, along with a graphic score I made for her to interpret. She did this with lots of composers. That’s one way.

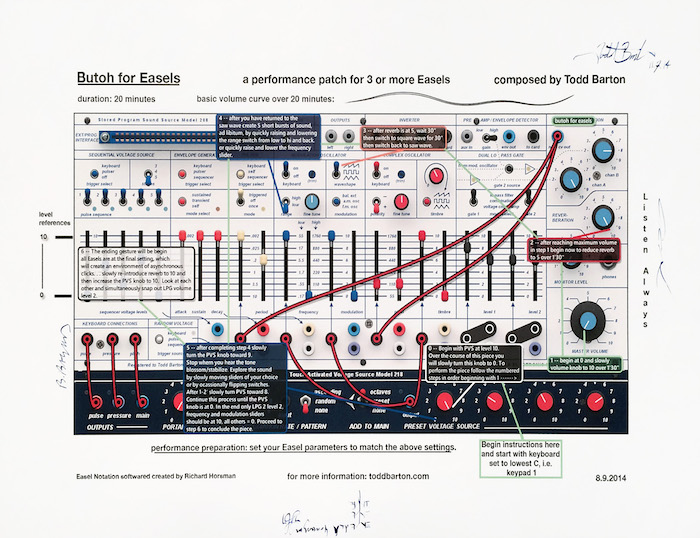

When I’m writing an acoustical score and I write middle C, I know how the flute player is going to finger it to get that note. I can add extended techniques to it, but it’s still going to sound like a C. On a synthesizer it’s a different story, especially with different setups. Let’s say I’ve got a EMS Synthi, you’ve got a Buchla, and my friend has a Hordijk, and somebody has some weird collection of Eurorack stuff. There’s no telling if everyone has the components to do the gesture I’m looking for. I did write a piece for four Music Easels, since the Easel is designed as a complete instrument. That’s something like, “Ok, we start with these knobs set at these marks, and we take two minutes to fade in these sounds, and then we’re gonna take forty five seconds to change the setting on the reverb, which is going to change the sounds dramatically, and then there might be points of free randomness for a minute, but we’re all gonna go back toward this next setting of the sliders and knobs.” In a way, it was as specific as when I used to write for acoustic instruments. But that’s only possible if you’re all working with the same instrument.

Can you tell me a little bit about your drawings? Do you see this as a parallel practice or does it inform your music?

It began as postcard art, about ten years ago, when my mentor and good friend was diagnosed with prostate cancer. We both love fountain pens and the way ink flows when writing or creating art, so we swapped postcards every day for at least three or four years. It began as a form of therapy. I don’t consider myself a visual artist, but I started on a journey. The good news is, he just turned 80, he’s in great shape, and still composing! The other aspect is my fascination with the work of Wassily Kandinsky. When I started, I hung up a big print of “Komposition 8.” I would just sit there for awhile and think about a dot. Where would the most interesting place for another dot be? I’d add a line, maybe a triangle. I think I was remixing “Komposition 8” in my own way. Kandinsky worked in charcoal, oils, acrylic, pastels, pen and ink. I started exploring different media. I did that every day for years, and I think I’m happy with some of what I did. (laughs) When I make music, I’m sculpting sound. When I make a drawing, I’m sculpting ink.

I think I read recently that the first Buchla design was a lamp, a rotating disc with holes in it, and a photoresistor. So from the very beginning the synthesizer had an “eye” in it, a connection to visual phenomena.

I think whether it’s dance, poetry, music, it’s all just sculpting energy. Of course, it can take a little while to get your technique together!

———————————————

Thanks to Todd Barton, Peter Harkawik, and RVNG Intl. for facilitating this interview.

Text has been condensed and edited for clarity.