Phew has had a decade-spanning, genre-hopping career and has cemented herself as an experimental music icon. She was a member of Aunt Sally, a punk band at the heart of the Kansai No Wave scene, and has collaborated with an incredible list of musical luminaries. Her

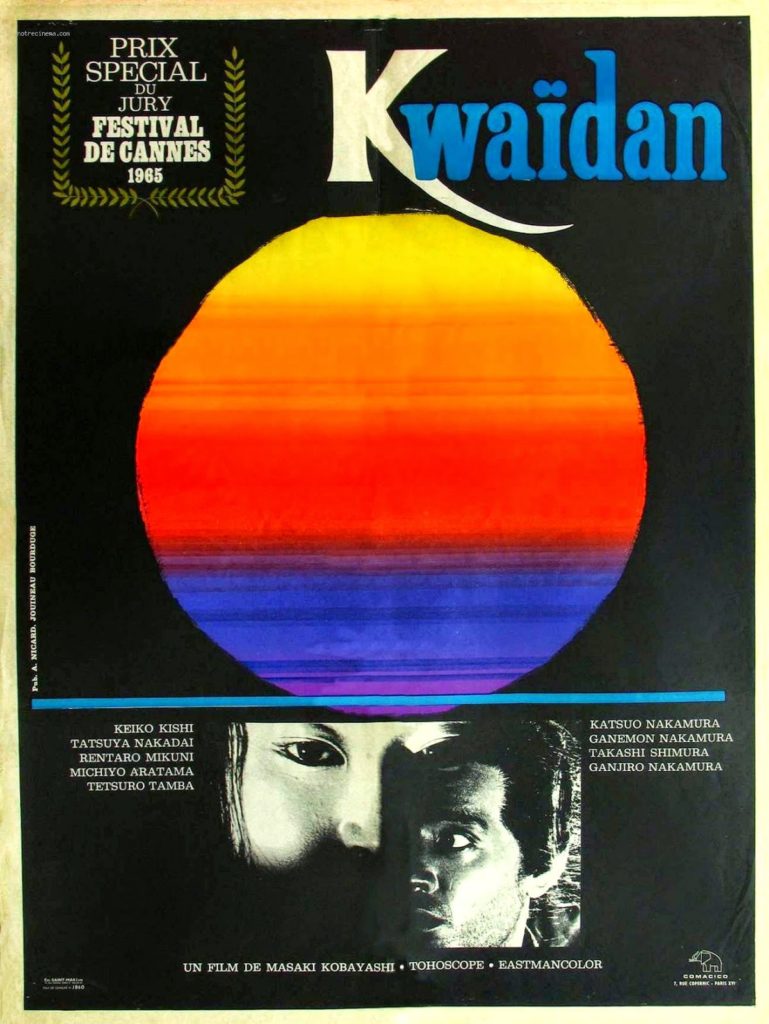

debut self-titled record from 1981 has been canonized by Japanese record collectors and post punk devotees alike. Still, it’s perhaps now, working with only her collection of analog hardware, that she’s at her most powerful. She has just released

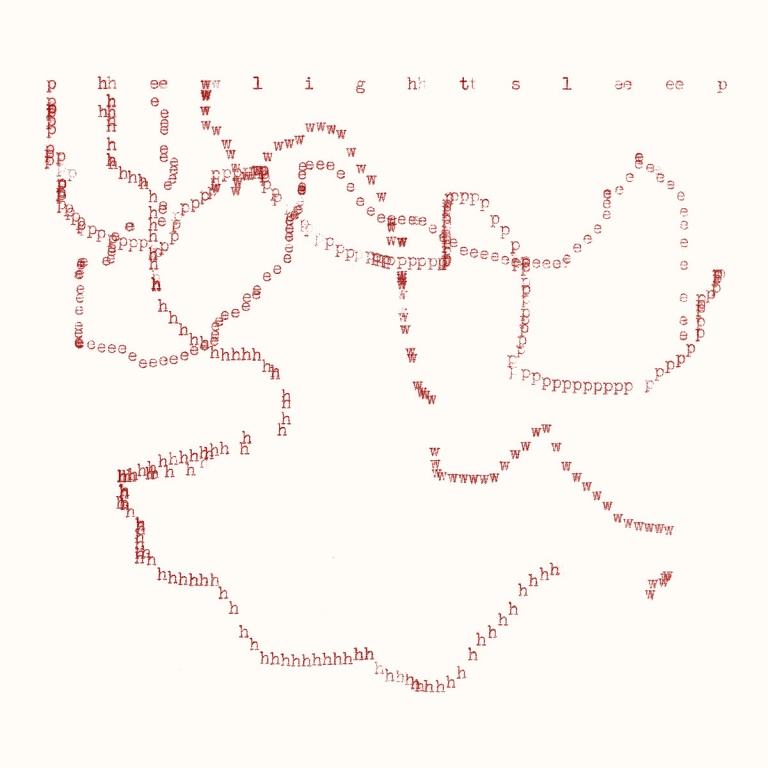

Light Sleep, a collection of six tracks culled from three CD-Rs that had previously only been available at her live performances. If you’re not yet familiar with her work, it’s an ideal place to jump in, and

you can buy it here. In conjunction with

Blank Forms, Phew will be making her US debut on April 6th at First Unitarian Congregational Church in Brooklyn.

Tickets are available here.

———————————————

You said in a recent interview that you wished you could “sing like dance, and use electronics like singing.” There’s some really beautiful footage online of you playing in Tokyo in 2014, and the whole thing sort of feels like a dance.

Thank you. For me, when I play live I’m definitely concentrating on the physicality of the performance. But I do have to be in control, although there is an element of merging—you treat the machines like an extension of your own body.

You’re committed to using analog gear instead of digital, but it’s of course harder to use and less predictable. Do you feel that the unpredictability has turned into a central part of your live performance?

Yes. I performed in Paris last night, for example, and it took about five minutes into my set to be able to match the sound I had been producing in sound check—but you just run with it. It’s definitely harder, but it’s also fun and satisfying to perform that way. To finally get the sound right is like catching a wild horse and making it your own.

How much room do you leave for improvisation and live composition during performances?

I go into it with a big sketch of what I want from a song, and from there it’s like filling in a coloring book. It’s never going to be the same twice, and that’s the fun part. If something’s not working, I’ll do something else.

You’ve also said that you don’t think you’re a singer in the conventional sense, because you don’t aim to communicate a story or incite feeling within the listener. It seems as if you’ve resisted ideas about what the voice “should” do as a “human instrument.” Still, your voice is really powerful and evocative. Do you feel you use voice as a texture, or even as a machine?

Yes—it’s definitely still an instrument, but the way I treat voice is hugely influenced by how I listened to music when I was a little girl. When I was ten or eleven years old, the Beatles’ Abbey Road came out, so I was listening to a lot of the Beatles without understanding any of the English. I was tasting voice in the same way as I would guitar, with no understanding of lyrical meaning. I’ve used voice that way ever since, texturally.

You’ve said that you hated the 80s in Japan—that everyone was drunk on money, and you didn’t even want to leave the house. It’s interesting because I imagine most people think of the 80s as a musical explosion for Japan, especially given what people were suddenly able to do with synthesizers.

I don’t know. I wasn’t even listening to contemporary music at the time. I was mostly listening to music from the ‘50s. A lot of Elvis Presley.

Right, you even did an Elvis cover. Did your parents listen to Elvis around the house while you were growing up?

No, they were listening to more jazz. Especially my dad. But I hated it—I was totally allergic to jazz.

Interesting! I would have guessed there’s a lot of avant-garde jazz influence in your music.

Maybe subconsciously. I feel better about jazz now, but if there are jazz influences in my music they’re unintentional.

You’ve also mentioned the Sex Pistols being a big influence on you as a teenager.

When the Pistols came out I was roughly the same age as their members. Seeing them live was influential, but it was less about their music specifically than about punk as a movement. UK punk was a huge influence in my desire to have a band, but Aunt Sally was less about making a political statement than embracing the possibilities of punk, musically. The main takeaway from punk, for me, was a lack of leadership, a lack of any “pop star” identity.

Has music ever been a form of protest for you?

In the 80s, it absolutely wasn’t. We were just making music. We never even thought about the fact that having three women in a punk band could be radical. Now, in 2017, it does feel more like a protest. But it’s less about having a specific message, and more about the live performance and considering the experience of the audience. There’s something very small and fragile about that relationship, and that’s the most important and radical aspect of making music for me.

A friend of mine recently pointed out that you’ve always gotten the best out of all the collaborators you’ve worked with over the years, playing to their strengths while still keeping the music balanced. It always sounds like you, even when you’re playing different genres. What do you look for in a collaboration?

I look for someone that changes me, someone that allows me change into something I didn’t expect. That’s the most exciting part. Surprise, flexibility.

A lot of people are referring to Light Sleep

as a return to the sounds of your first record. To me the sound feels more intimate and specific—the gestures feel smaller and more detailed, a lot of the beats feel like microbeats. It’s more delicate. Is this kind of intimacy a product of working without collaborators?

Yes. The recordings on Light Sleep were made before my record A New World. The songs are rough sketches, like drawing an object in pencil, which is probably the intimacy and scale that you’re hearing. I also recorded them in my bedroom, so they’re meant to be small.

Do you have plans or projects for when you’re done touring?

I want to do a performance in collaboration with a video artist. I’d like it to be somewhere in between a vocal performance piece and an installation, so it would probably be in a gallery or museum setting.

———————————————

Thank you to Phew, Juri Onuki, Cora Walters, Lawrence Kumpf, Keiko Yoshida, and Mesh-Key for facilitating this interview. Text has been translated, condensed, and edited for clarity.