Suzanne Ciani is a five-time Grammy award nominated composer, electronic music pioneer, and neo-classical recording artist whose work has been featured in countless commercials, video games, and feature films. A self-taught pianist with classical music training from The Longy School of Music and Wellesley College, Suzanne discovered electronic music in the late 60s and quickly became immersed in the worlds of sound synthesis and computer music. With her instrument of choice, the Buchla modular synthesizer, Suzanne revolutionized the advertising industry, and her sounds were featured in spots for General Electric, Sunkist, Clairol, and AT&T, amongst many others. Perhaps her most famous piece, the Coca-Cola “Pop n’ Pour” sound effect, was featured in hundreds of Coca-Cola commercials throughout the 70s and 80s. In the 90s, Suzanne transitioned from synthesizers back to the piano and formed her own record label, Seventh Wave. She’s been recognized as Keyboard Magazine’s “New Age Keyboardist of the Year,” provided the voice and sounds for Bally’s groundbreaking Xenon pinball machine, played concerts all over the globe, and carved out a niche as one of the most creatively successful female composers in the world. Her most recent release, Live Quadraphonic, is a live recording of Suzanne’s first solo Buchla performance in 40 years, released in quadraphonic sound on 180g vinyl and includes a hardware decoder to decode two channels of audio from the vinyl disc back to the four-channel recording, and can be purchased here.

Interview by René Kladzyk, a NYC-based musician, perfumer and geographer who performs under the moniker Ziemba. Her elemental orientation is decidedly watery these days.

———————————————

My entrypoint to your work was through Seven Waves, which I imagine is the case for a lot of your listeners, so I’m wondering if you can tell me about the conceptualization and creation of that record.

Seven Waves was my first album, and I had waited years to do it because I had to be in a position to afford to make it. By the time I got there, my vocabulary had changed. I had stopped doing pure Buchla, and I was frustrated that the public didn’t understand the music technology. The whole analog thing was a little too abstract. My roots were classical, so without much thought process what happened naturally with Seven Waves was that I synthesized my classical roots with my technological background, my ten years working with the Buchla. That’s the vocabulary of that album: it’s romantic and melodic. I wanted to make technology sensual because I was making the music for myself and I wanted to feel relaxed, calm, happy and safe, and to create an immersive space that I could just be in. It took two years, partly because I could only work on it on weekends, and partly because it was expensive, and I had to do things as I could afford them.

I call the compositions waves, because each piece starts slowly and builds to a climax and then recedes in the shape of wave. I made waves on the Buchla of course, and each wave had a special personality for the piece. In the end I connected all the pieces so that they flowed in and out of the waves as one long uninterrupted piece. It was entirely electronic, and I thought of each of the electronic instruments as musicians in a way, so I credit every instrument–

Every instrument! (laughing)

Every instrument, including reverb and things like that, because it was all an essential part of the sound. I remember that in the early pieces, the notes were entered in a Roland MC4 or an MC8, do you know that?

I don’t.

Well, almost all of the music was written out, and for each note you had to put in a number for the pitch, a number for the duration, and a number for the volume. A lot of it was a very painstaking, and some of it was just flourishes where you create a gesture in the moment. I had a commercial music business by then, and my business partner was named Mitch Farber. Mitch was this wonderful guy, a jazz arranger and a great go-to guy for doing layouts. I would write out the music on my piano, but we needed a layout on score paper because there was so much information to enter. All these numbers had to go beside every note. He did the layouts of the score in the music paper, and I have those scores in a book. It’s not the type of score where you could perform it per se because…well I guess you could–

Would you ever consider doing something like an orchestral Seven Waves performance?

It could be orchestrated.

Both in the context of Seven Waves but also more broadly, so much of the symbolic and poetic language around you is watery and associated with waves. Has your elemental orientation shifted at all over time? Do you think about the current work that you’re doing with quadraphonic Buchla in a similar type of symbolic language?

It’s a different vocabulary, but the waves are there. My concerts always start with the waves because that’s where I’m comfortable, and the music rises out of the waves. That’s always been my approach. So the waves still figure in my work, though I don’t approach performance classically, the way I did with Seven Waves. It’s still note and pitch based, but much more loosely. I think of it more as jazz than classical: it’s more improvisational and in the moment, working with the machine and getting the feedback from the machine. As I do these performances, certain things start to settle and become familiar, but the experience is always a little bit unexpected. I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do.

Do you have any guiding intentions or rules for how you approach these more improvisational performances you’ve been doing recently?

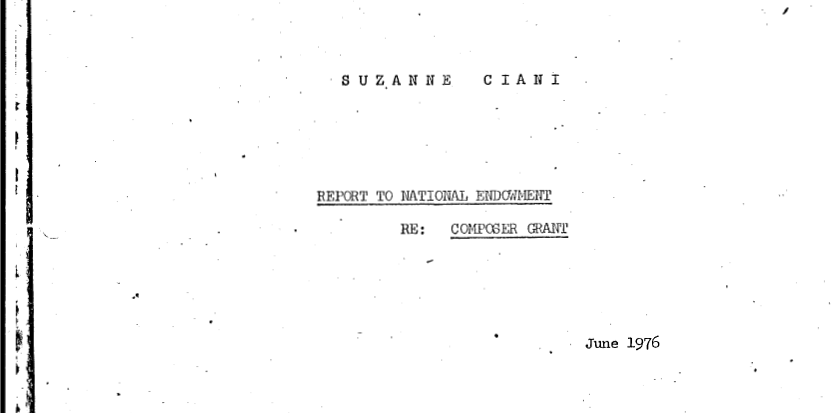

When I came back to this genre, this idea, I consulted a paper that I wrote 40 years ago.

I tried to track down that paper on the internet, actually. You referenced it in an interview, and I was like, “I wanna read that!”

Oh yeah? It’s in the Finders Keepers LP liner notes, for The Buchla Concerts 1975. Andy Votel, who published it, included the paper.

Suzanne has kindly shared this paper, which she calls The Buchla Cookbook, with us.

Suzanne has kindly shared this paper, which she calls The Buchla Cookbook, with us.

This is the first time this paper has been made available online.

So I use the same sequences that I used in the 70s: four 16-stage sequences. I also still use a lot of the techniques that I developed over my years of playing the Buchla.

One of the things that I think is so special about the quadraphonic performances you’re doing is how spatially specific they are. I’m wondering if you can describe the space you’re trying to create with these performances in non-musical terms? Like, what does it look like to you, or feel like, or smell like…

Spatial control was always part of the Buchla, so from the beginning we worked in both quadraphonic space and imaginary space. You could create big, small, close, far away, all that, as part of the music. It’s different from a lot of spatial manipulations nowadays, where it’s mapped onto the music in post-production. The Buchla actually generates spatial characteristics, so it’s rhythmically in sync with the music. I use different kinds of space for different kinds of things, instinctively–sometimes it’s a continuous space, sometimes it’s a discrete space, jumping around in a different rhythm. And it’s alive. Without the space there’s nothing, because the output of this type of machine is essentially monophonic. Stereo was fabricated to spread things out over a span; it wasn’t meant to move sound. Quadraphonic in electronic language is meant to be a parameter, like pitch and volume and rhythm, so it’s really part of the music.

It’s all about the motion of it–

It’s all about the motion. I always say that, with the Buchla, it’s not about the sound, but the way the sound moves. And Don knew that. We weren’t trying to imitate a sound or make an amazing sound and then play it on a keyboard. The sound was a byproduct of the way it could move. So you have voltage control, with which you could move the sound quickly, slowly, whatever, and the sound changes with the movement.

That was something I was really struck by when I saw you perform in New York. I think I told you after the show that it felt like an ecosystem. The nature of how it was alive with so many different characters, and the chaos in it–it felt very organic to me. I’m curious what some of your nonmusical creative influences are.

Well, I have art roots. My sister is a visual artist, and I grew up in the art world. My first projects were with sculptors: Harold Paris, Ron Mallory, Joseph Robinson. Maybe people you don’t know, but Ron worked in mercury, and we did a film called Lixiviation, which then became the title of the album that Finders Keepers released—

Oh, I heard the album but didn’t know it was a film soundtrack.

Yeah, that’s where it came from. I’ve also worked with dancers. Nature and the sea are very big inspirations. One of my spiritual mentors was a photographer, Ilse Bing, who was from Germany. I met her when she was in her 80’s and I was in my 30s.

She was a mentor to you?

She was, because she was a true artist, and she worked in technology. She was called the “Queen of the Leica” and I’m the “Diva of the Diode.” She was a brilliant woman who worked in a man’s world and had this incredible edge. She discovered solarization before Man Ray, and she never got credit for it. She had a very successful career, and she was somebody that I could talk to about my work. She was an intellectual, and she always would say, “Tell me, tell me about your work!” I always wanted to talk about my boyfriends, but she kept me focused. So I had such an identification with her, as you do with a mentor. Who knows what mentoring is, or how that happens. She just was. It’s who she was.

It just happened naturally?

Yes, it happened naturally. I collect her work, so I have a huge collection of her photographs. I collected them before I even knew her. When she was 60 she stopped photographing, and it was a total crisis for me, because I was young and idealistic. I thought, “How can you?” I didn’t understand, because I saw myself as somebody who was going to go forever in my art. What I’ve realized in maturity was that she didn’t stop her art, she just shifted gears, kind of like the way I shift gears. There might be people who are disappointed that I’m not playing the piano right now, and making my romantic music, but I’m doing what I do!

That’s actually something that I wanted to ask you about. Can we talk about love a little bit?

Sure. I don’t think I know anything about it, but sure.

Well, there’s so much romance and sensuality in so much of your work, but–this was the trickiest question for me to formulate. I wanted to talk to you about love as a concept, but also romantic music and the different ways of expressing it, and whether with the compositional approach you have now, you’re intentionally moving away from a romantic expression.

Well, yes! I think when you’re young and you have all those hormones, and you’re into that trajectory of finding your prince and all that, that’s a certain energy system. It’s wonderful, but it doesn’t last forever.

Like the planet Venus ideological approach.

Right! And what you find out, or what I found out as I was older, is that I love, but I don’t love in that focused, one person or one place kind of way. It’s more open now. There’s still love, but it doesn’t have to be that–what is that–the symbolic or male/female…

Movie love?

Movie love! (laughing) I love romcoms. I love the whole idea of love, and my favorite guy, what’s his name? The British guy that does all the…

Colin Firth?

No, the British guy that does all the romantic comedies.

Hugh Grant?

Yes! I love Hugh Grant, and I don’t know why! Because he doesn’t fit any of my images of an ideal. I just like his spirit, I guess. So yeah, I did have a divorce and it was a bit of a crisis because I had the perfect marriage in a way. It really was the crystallization of the utter total fantasy of love. Then when it broke, it was devastating. At the same time, I think I outgrew that idea of love. So I’m happy, I’m not looking for anything, and I think I found it! (laughing) And I love it all. I think it’s wonderful when you’re young. It’s a rough ride–it can work synchronously, sometimes perfectly, but most of the time it’s filled with illusion and bumps. But it’s worth it.

It is worth it. If I can ask one last thing, I was wondering if you have any advice you’d like to offer to women working in the music industry, or even in the art world.

We’re on the crest of a wave right now, and it’s a very important historic time for us. I haven’t seen this type of energy since the 60s, when we had another crest of the wave. Everything is waves. So now that we’re on the crest, I say don’t forget. Go with it, be yourself, take your rightful place. If you’re looking for validation as an artist, the only authentic place to start is with yourself. You must meet your own standards of excellence, because no one outside yourself can corroborate your artistic message. Women have trouble with self confidence because they’ve been trained to believe themselves to be lesser. It’s a very insidious thing. You have to remind yourself that you’re never less than. We also need to learn how to respect other women. Because women don’t even respect women.

I think women are trained to turn on each other on a dime, and are very competitive with each other in ways that aren’t necessarily helpful.

But you know why? It’s because we’re playing in a different playing field. We used to be competing with men, and we were trying to get an edge there. We’re not doing that anymore. We’re competing with each other instead of with men; and we’re not trying to take over a man’s world, we’re creating our own world. It’s wonderful; it will be a world equal to the man’s world, and different. We’ll support each other; we just need to respect the talents and the abilities of women, and to respect ourselves also. We’re having a very important and formative moment right now. We’re making a shift amongst ourselves and in the world.

———————————————

Thanks to Suzanne Ciani, René Kladzyk, Rachel Aiello,

and Matt Johnstone for facilitating this interview.

Text has been condensed and edited for clarity.