|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

Tag: electronic

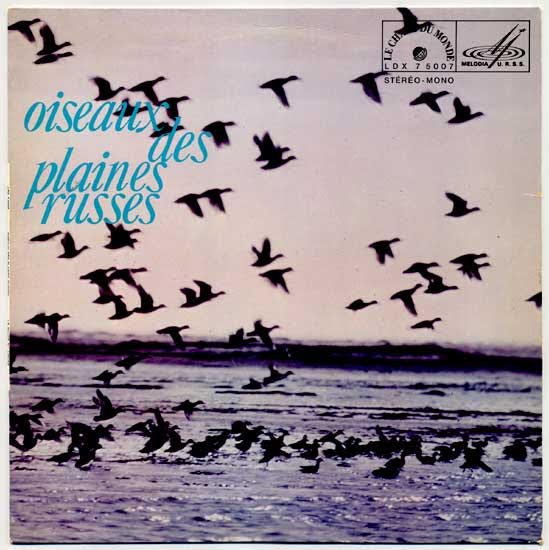

Guest Mix: Oiseaux des Plaines Russes

Guest mix by DBGO (Soundcloud / YouTube / Playmoss)

This is a selection of music composed by USSR artists from 1976 to 1995. The cover picture has been taken from the cover of the album Oiseaux Des Plaines Russes by Борис Вепринцев. I prepared this playlist right after my second (Ella) was born and during pandemic times, hope you enjoy it.

Previous mixes from DBGO: Vojtěch a Irena | A caballo, Tarumba | Où est allé le temps, 2ème Partie | Où est allé le temps, 1ère Partie

Tracklist:

1. Collage – Kodu Kaugel (1978)

2. René Eespere – Unemaal (1987)

3. Ilona Papečkytė – Šuliny Šaltini (1992)

4. Echidna Aukštyn – Echidnos Sesija Su M.Litvinskiu (3 Dalis “Kleboniškis”, Fragmentas) (1995)

5. Heino Jürisalu – Unelaul (1977)

6. Ленинградский Джаз-Ансамбль – Ария (1976)

7. Sven Grunberg – Hästi (1979)

8. Асфальт – Тихая Песня (1990)

9. Влади́мир Тара́сов – Монотипии IV (1986)

10. Kuriokhin & Kaiser – Frozen Reflection (1989)

11. Владимир Рацкевич & Олег Литвишко – Action (1992)

12. Giedrius Kuprevicius – Erotidijos (Part 8)

13. Giedrius Kuprevicius – Berceuse first computer version (1996)

14. Wejdas – Nežinomiems Dievams (1994)

15. NSRD – Vakars Aiz Priekšējā Stikla (1988)

16. Sven Grunberg – Ka Siber (1990)

17. Vidmantas Bartulis – Du Klausimai Laukinės Slyvos Medžiu – Apie Meilę (1986)

18. Борис Вепринцев – Rouge-gorge (Erithacus Rubecula) (1967)

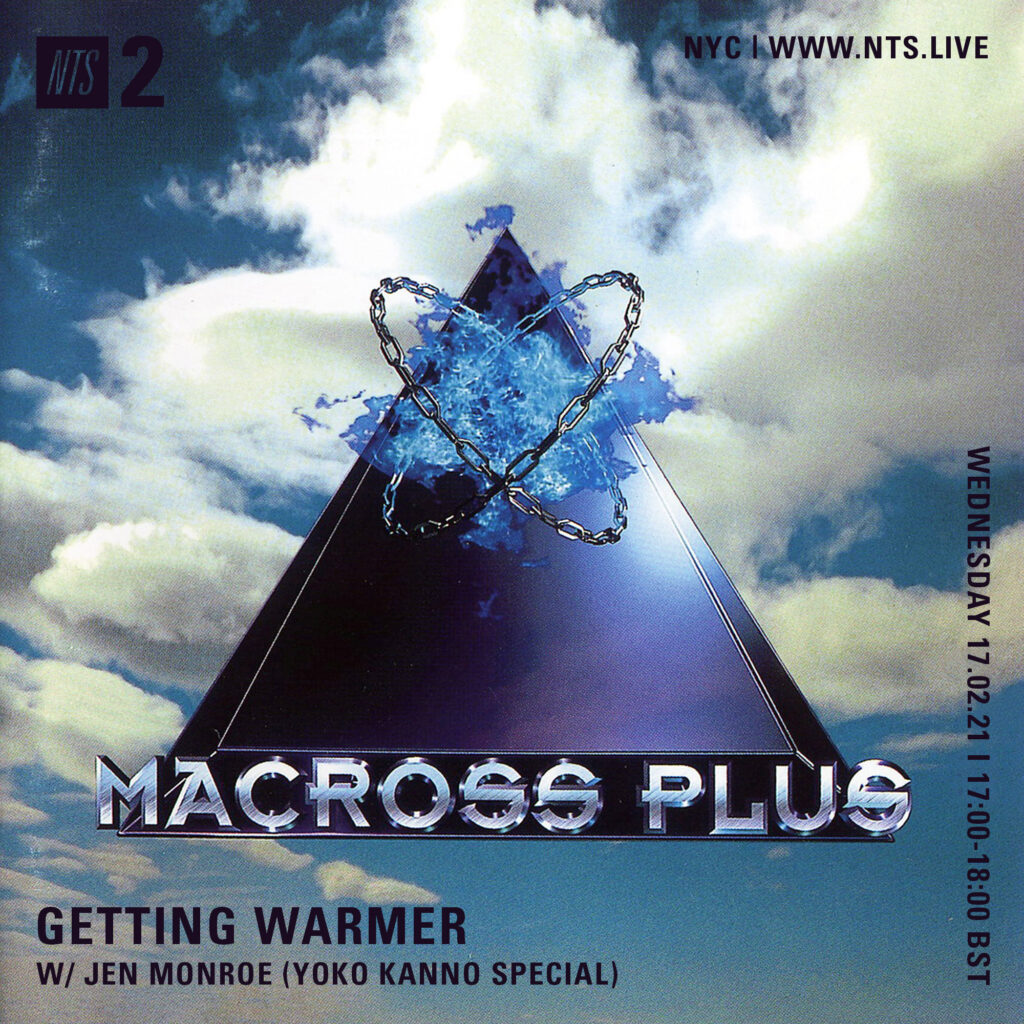

[Mix for NTS Radio] Getting Warmer Episode 52: Yoko Kanno Special

My newest mix for NTS Radio is an hourlong Yoko Kanno special. If you’re unfamiliar, Kanno is a Japanese composer, arranger, and musician. best known for her extensive work soundtracking anime films and series, though she’s also scored a number of video games and live-action films. Some of her noteworthy anime scores include Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Cowboy Bebop, Macross Plus, Turn A Gundam, The Vision of Escaflowne, Darker than Black, Wolf’s Rain, and Terror in Resonance. My entrypoint to her work, as I suspect is the case for many, was the terrific theme for the Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex series, “Inner Universe,” which is sung in Russian, English, and Latin by Japanese-Russian singer Origa, who is a regular collaborator of Kanno’s. Since then it’s been a joy to dig through her enormous discography, so I’ve compiled a few of my favorite moments here, ranging from opiated trip hop and jazz to sweeping cinematic modern classical to devastating choral pieces and churning dystopic breakbeat. I hope you like it! You can download an mp3 version here.

Tracklist:

1. Yoko Kanno – Blue Tone

2. Yoko Kanno – Stamina Rose

3. Yoko Kanno – Pulse

4. Yoko Kanno – 縮緬エアー

5. Yoko Kanno – Chorale

6. Yoko Kanno – Go DA DA

7. Yoko Kanno – She Is

8. Yoko Kanno – Some Other Time

9. Yoko Kanno – Bang Bang Banquet

10. Yoko Kanno – Aqua

11. Yoko Kanno – Orphan

12. Yoko Kanno – On The Earth

13. Yoko Kanno – A Sai En

14. Yoko Kanno – This EDEN

15. Yoko Kanno – Ephemera

16. Yoko Kanno – Bells For Her

17. Yoko Kanno – The Clone

18. Yoko Kanno – Torch Song

19. Yoko Kanno – Siberian Doll House

20. Yoko Kanno – Inner Universe

Goddess In The Morning – Goddess In The Morning, 1996

There’s a significant chance you’ve already heard half of this record, as I’ve regularly been using it in mixes for the past year and a half. And with good reason! Aside from being objectively beautiful from start to finish, it feels particularly aesthetically situated to resonate well with listeners right now, so I wouldn’t be surprised if this prompts a reissue. (Do it!)

It’s a mysterious record–the only release from the eponymous duo Goddess In The Morning, comprised of Akino Arai and Yula Yayoi. Akino has left a pretty dense paper trail, credited on 95 different releases for vocals, writing, arrangement, and production, notably as a regular contributor to Yoko Kanno scores. Yula is a little harder to trace, with a handful of releases that I’ve had limited success in tracking down. I’d particularly love to hear her 1999 record Summer Aura on the basis of its cover art and release year alone, if anybody has a copy they’d be willing to share. (She also shows up as a vocalist on Seigén Ono‘s behemoth 20-disc Saidera Paradiso, and fittingly, Ono is credited with mastering Goddess, which seems particularly cool in light of how divergent the record is from Ono’s wheelhouse.)

Goddess In The Morning is a wild ride in the truest sense, ranging from hazy trip hop on “Ucraine” to the Celtic folk-inspired prog “Saga” to the Virginia Astley-esque pastoral closer “14.” Across them all are (what I assume to be) Yula and Akino’s heavily layered vocals (effectively musical catnip for me), processed into intricate electronic landscapes that feel both spacious and heavily polished to a reflective chrome sheen. I’m not gonna try to sell this too much harder, because if it’s for you, it’s very obviously for you, but I do hope you love this, as it keeps worming its way nearer (and dearer!) to my heart.

15 Favorite Releases of 2020

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

|

|

buy / download |

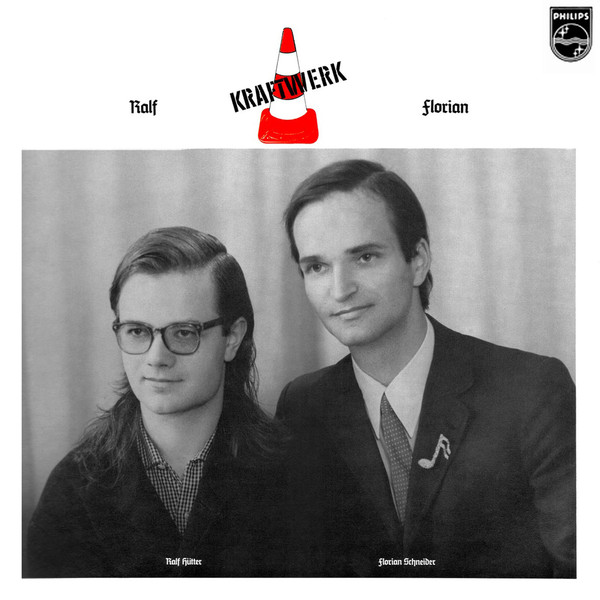

[RIP] Kraftwerk – Ralf Und Florian, 1973

Like many others, I was deeply saddened to wake up this morning and learn of the passing of Kraftwerk’s Florian Schneider. I was delighted, however, to read an anecdote today that he built a giant speaker in his yard so he could listen to Bach while he mowed the lawn. While it feels trite to express a sentiment that’s currently flooding my Twitter timeline, it’s amazing to reflect on a collective experience shared by so many: the recollection of first hearing Kraftwerk as a teenager, and in spite of not being able to properly contextualize it because of how normalized and mainstream electronic music was at the time (2005 for me), still feeling a very specific and novel joy. Like many others, Kraftwerk was a musical gateway drug, and slowly understanding the depth and breadth of their influence on so many subsequent musicians who I’ve loved has been a consistently sweet experience that has continued through adulthood. We will probably never stop noticing glimpses of Kraftwerk in the most unexpected places, and it will always feel like a gift, like finding an arrowhead half-buried in the sand at the beach.

I wanted to share Ralf Und Florian today because while it is considered a classic, I think many of those familiar with Kraftwerk in a cursory way might never have heard it. It’s from 1973, a decade I didn’t associate with Kraftwerk at all as a kid, but it turns out they were busy being ahead of their time way ahead of their time. Amongst their early releases this one is considered a kind of turning point, during which they moved away from the more scraggly krautrock of their first two records and started exploring sounds that were unafraid to be obviously beautiful. They hadn’t yet become quite so dogmatic about electronics, and so Ralf Und Florian sits in a really beautiful midpoint between analog and electronic instruments, mixing flute, chimes, and strings with drum machines and synthesizers.

I love that much of this record is technically ambient (a piano–yes, a real one, and flute [!] are the bulk of the gorgeous “Heimatklänge,” without any percussion in sight [!]), and I love how much of it is cosmic in the literal sense–not laden down with guitar, kosmische, but light and luminous like the cosmos. Lap steel guitar and pastel sunsets. Glittering tiny chimes. What is so striking about Kraftwerk throughout their entire discography is that in spite of wholeheartedly embracing a futurist cyborg ethos, their music always sounds so warm–an adjective very at odds with the metallic, impersonal, hard, icy associations with electronic music. They always sound so human, in spite of everything.

I hear that the most on my favorite, “Tanzmusik” (which translates, so sweetly, to “Dance Music,” though to me it also sounds like the overwhelming joy of driving through the carwash, or like hot summer rain). It’s extremely sparkly, layered with diving wordless vocals and handclaps (both of which remind me a lot of early Animal Collective, speaking of finding influences in funny places). But that human warmth is all over this record. In fourteen minute long closer “Ananas Symphonie” (pineapple symphony!), you hear psychedelic Hawai’i exotica through an obviously German lens, with shimmering lap steel guitar, ocean waves, and the beginnings of their fixation on vocoders. It is extremely relaxing, an adjective many might not associate with Kraftwerk–percussion, when present at all, is only soft pulsing.

I don’t want to say too much more about it since so many others have already said it much better than I could, but I’ll reiterate that the musical world would look very different today–perhaps unrecognizably so–had Florian (und Ralf!) not been in it. Thank you for everything, Florian.

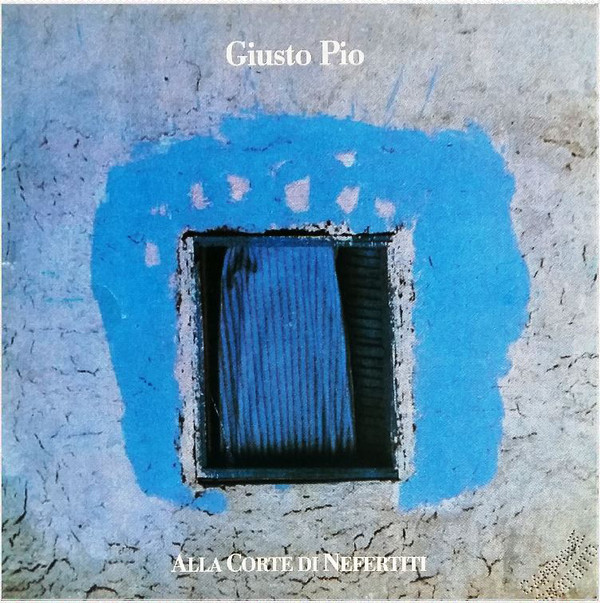

Giusto Pio – Alla Corte di Nefertiti, 1988

Pristine minimal ambience from Italian musical giant Giusto Pio. Best known for his many collaborations with Franco Battiato, Pio was a composer and world class classical violinist born in Castelfranco Veneto in 1926. He was sought out by Battiato as a violin teacher, but the two went on to sculpt Battiato’s sound from post-prog to minimalism to Europop, with many other projects along the way, like their contributions to this Francesco Messina record. Among these collaborations, Battiato produced Pio’s first solo album, considered to be Pio’s crowning achievement and a holy grail of avant-garde minimalism: 1979’s Motore Immobile. Pio continued to release solo records until 1995. He passed away in 2017 at the age of 91.

Alla Corte di Nefertiti, however, is a very different beast. Though it was released by Battiato’s publishing company L’Ottava S.r.l. as a subsidiary of EMI Records, Battiatio wasn’t involved in production. The record is two long-form tracks of synth impressions, the first of which is more of a holistic composition and the second of which is a reflection, or “frammenti,” of the first, sonic pieces broken up and scattered with spaces falling where they may. I like the more pure minimalist moments the best, where single vibrating tones are left to hang in the air like washes of color, but there are also some great moments with synthetic choirs of angels radiating concern from plastic celestial bodies. A few moments of percussive texture, some which have a cinematic urgency that feels appropriate for Pio’s background, but for the most part Alla Corte di Nefertiti is just drifting in pillows of sound. Made on an Akai MG1212. Excellent for working to, or waking up to. Thanks for all the music, Giusto.

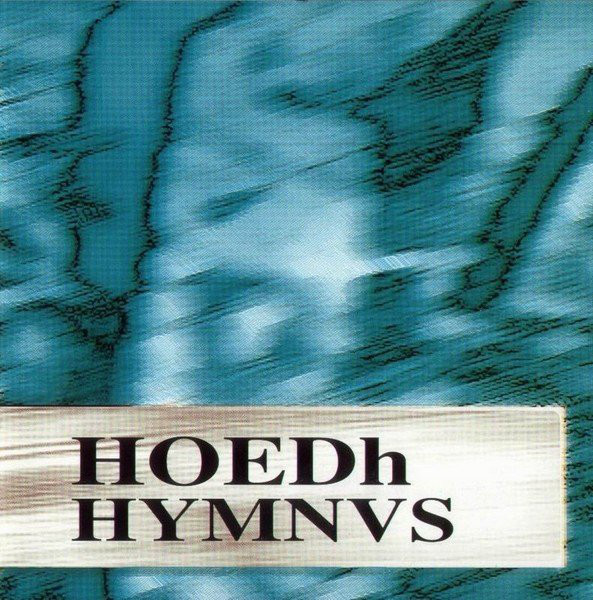

Hoedh – Hymnvs, 1990

Peak dark ambient. The first of two solo records from German trance and ambient musician Thorn Hoedh, who passed away in 2003. Equally lauded as a holy grail of the genre and bemoaned as an overlooked masterpiece, Hymnvs manages to be both sprawling and claustrophobic; cinematic and lo-fi; inorganic and classical. If you’re not paying attention, these seven long-form tracks (or hymns) might appear like a flat and unchanging expanse of black tones, but a few seconds in headphones proves otherwise–there’s actually a great deal of intricate movement happening beneath the surface, so much so that tracks like “Das Geistige Universum” seem to actually evoke the nausea of being pitched around in a boat in choppy water. Elsewhere, ringing overtones and expansive, bending pitches, as on “Hoedh (Sonnenklang)” are completely sonically disorienting. There is, in short, a lot going on here.

I love the anonymity of the instrumentation–it’s frequently unclear whether we’re listening to an acoustic instrument that’s been modified, or to a synthetic interpretation of an instrument. Still, the sounds are warped around the edges in familiar ways: “Heilige (Mantra Der Rotation)” has the gape of wind instruments in a massive tunnel; other tracks feature synthetic remnants of strings, piano, horns; but always we feel a certain kind of crackling closeness that can’t simply be attributed to lo-fi production (though there is a distinct feeling of of well-worn vinyl). It’s as if the sounds have had tiny shading details painted onto them by very meticulous hands.

It seems as if listeners have consistently ascribed a deep and impenetrable melancholy to Hymnvs, and it’s true that it imparts a feeling of descent, or even of disassociation. But if listening to this record is the sensation of slowly sinking backwards into water while looking up at the receding surface, then inevitably there are beams of light penetrating the surface, sun-dappled and speckled with dust motes, which is to say that Hymnvs is flecked with joy, with optimism, as the best hymns are. For fans of The Caretaker, Gavin Bryars, William Basinski, or, uh, Wagner.

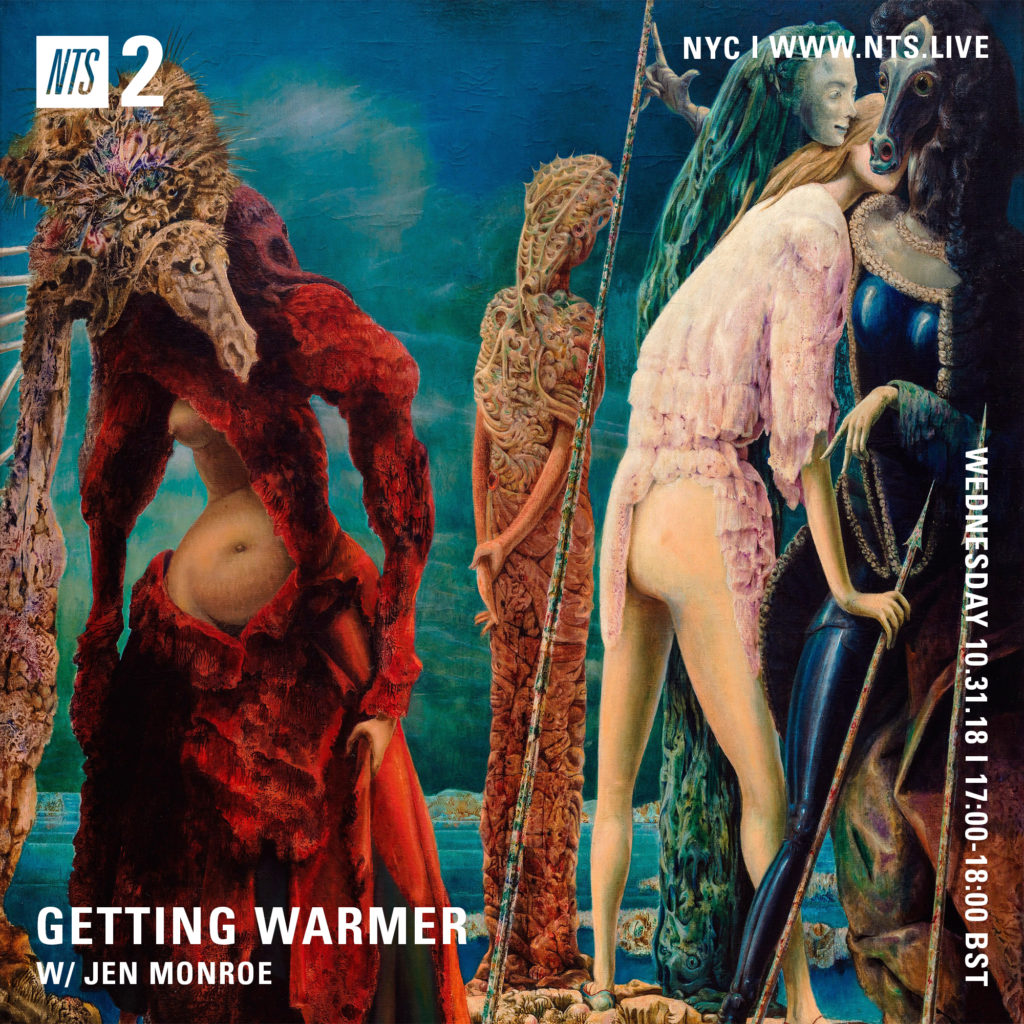

[Mix for NTS Radio] Getting Warmer Episode 29: Halloween Special

Please enjoy this Halloween special of Getting Warmer for NTS Radio. Featuring overtones, appalachian folk, Tibetan chant, a Delia Derbyshire side project, baroque psych, Kwaïdan, Throbbing Gristle, and lots more. You can download an mp3 version here.

Just a note that there are some things in here that are startling and disturbing, or at least I think so, so if you don’t like listening to scary things I would suggest giving this one a pass.

Tracklist:

1. Buffy Sainte-Marie – Poppies

2. David Hykes & The Harmonic Choir – Gravity Waves

3. Dorothy Ashby – The Moving Finger (excerpt)

4. White Noise – Love Without Sound

5. Karen James – Ghost Lover

6. Throbbing Gristle – Hamburger Lady

7. Ghedalia Tazartès – Une Voix S’en Va

8. Syd Barrett – Golden Hair

9. Monks of the Monastery of Gyütö – Sangwa Düpa (excerpt)

10. Geinoh Yamashirogumi – Osorezan (excerpt)

11. Tōru Takemitsu – II. Yuki (The Woman of the Snow)

12. Anna Homler & Steve Moshier – Sirens (excerpt)

13. Lead Belly – In The Pines

14. The Caretaker – My Heart Will Stop In Joy

15. Dead Can Dance – Wilderness

16. Dorothy Carter – Along The River

17. Jean Ritchie – The Unquiet Grave

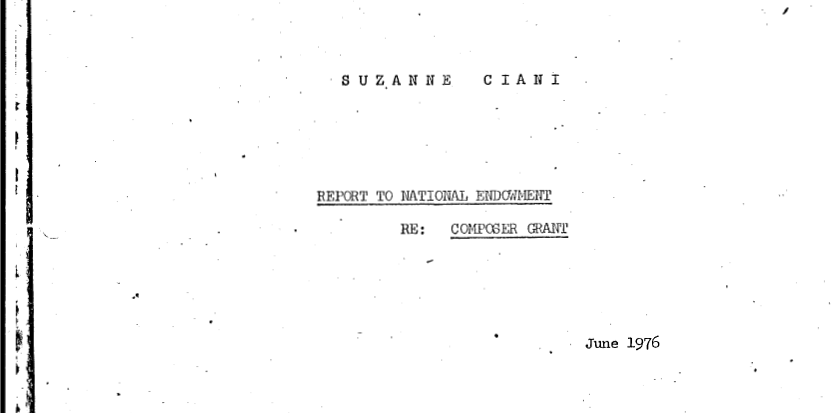

[Interview] Suzanne Ciani

Suzanne Ciani is a five-time Grammy award nominated composer, electronic music pioneer, and neo-classical recording artist whose work has been featured in countless commercials, video games, and feature films. A self-taught pianist with classical music training from The Longy School of Music and Wellesley College, Suzanne discovered electronic music in the late 60s and quickly became immersed in the worlds of sound synthesis and computer music. With her instrument of choice, the Buchla modular synthesizer, Suzanne revolutionized the advertising industry, and her sounds were featured in spots for General Electric, Sunkist, Clairol, and AT&T, amongst many others. Perhaps her most famous piece, the Coca-Cola “Pop n’ Pour” sound effect, was featured in hundreds of Coca-Cola commercials throughout the 70s and 80s. In the 90s, Suzanne transitioned from synthesizers back to the piano and formed her own record label, Seventh Wave. She’s been recognized as Keyboard Magazine’s “New Age Keyboardist of the Year,” provided the voice and sounds for Bally’s groundbreaking Xenon pinball machine, played concerts all over the globe, and carved out a niche as one of the most creatively successful female composers in the world. Her most recent release, Live Quadraphonic, is a live recording of Suzanne’s first solo Buchla performance in 40 years, released in quadraphonic sound on 180g vinyl and includes a hardware decoder to decode two channels of audio from the vinyl disc back to the four-channel recording, and can be purchased here.

Interview by René Kladzyk, a NYC-based musician, perfumer and geographer who performs under the moniker Ziemba. Her elemental orientation is decidedly watery these days.

———————————————

My entrypoint to your work was through Seven Waves, which I imagine is the case for a lot of your listeners, so I’m wondering if you can tell me about the conceptualization and creation of that record.

Seven Waves was my first album, and I had waited years to do it because I had to be in a position to afford to make it. By the time I got there, my vocabulary had changed. I had stopped doing pure Buchla, and I was frustrated that the public didn’t understand the music technology. The whole analog thing was a little too abstract. My roots were classical, so without much thought process what happened naturally with Seven Waves was that I synthesized my classical roots with my technological background, my ten years working with the Buchla. That’s the vocabulary of that album: it’s romantic and melodic. I wanted to make technology sensual because I was making the music for myself and I wanted to feel relaxed, calm, happy and safe, and to create an immersive space that I could just be in. It took two years, partly because I could only work on it on weekends, and partly because it was expensive, and I had to do things as I could afford them.

I call the compositions waves, because each piece starts slowly and builds to a climax and then recedes in the shape of wave. I made waves on the Buchla of course, and each wave had a special personality for the piece. In the end I connected all the pieces so that they flowed in and out of the waves as one long uninterrupted piece. It was entirely electronic, and I thought of each of the electronic instruments as musicians in a way, so I credit every instrument–

Every instrument! (laughing)

Every instrument, including reverb and things like that, because it was all an essential part of the sound. I remember that in the early pieces, the notes were entered in a Roland MC4 or an MC8, do you know that?

I don’t.

Well, almost all of the music was written out, and for each note you had to put in a number for the pitch, a number for the duration, and a number for the volume. A lot of it was a very painstaking, and some of it was just flourishes where you create a gesture in the moment. I had a commercial music business by then, and my business partner was named Mitch Farber. Mitch was this wonderful guy, a jazz arranger and a great go-to guy for doing layouts. I would write out the music on my piano, but we needed a layout on score paper because there was so much information to enter. All these numbers had to go beside every note. He did the layouts of the score in the music paper, and I have those scores in a book. It’s not the type of score where you could perform it per se because…well I guess you could–

Would you ever consider doing something like an orchestral Seven Waves performance?

It could be orchestrated.

Both in the context of Seven Waves but also more broadly, so much of the symbolic and poetic language around you is watery and associated with waves. Has your elemental orientation shifted at all over time? Do you think about the current work that you’re doing with quadraphonic Buchla in a similar type of symbolic language?

It’s a different vocabulary, but the waves are there. My concerts always start with the waves because that’s where I’m comfortable, and the music rises out of the waves. That’s always been my approach. So the waves still figure in my work, though I don’t approach performance classically, the way I did with Seven Waves. It’s still note and pitch based, but much more loosely. I think of it more as jazz than classical: it’s more improvisational and in the moment, working with the machine and getting the feedback from the machine. As I do these performances, certain things start to settle and become familiar, but the experience is always a little bit unexpected. I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do.

Do you have any guiding intentions or rules for how you approach these more improvisational performances you’ve been doing recently?

When I came back to this genre, this idea, I consulted a paper that I wrote 40 years ago.

I tried to track down that paper on the internet, actually. You referenced it in an interview, and I was like, “I wanna read that!”

Oh yeah? It’s in the Finders Keepers LP liner notes, for The Buchla Concerts 1975. Andy Votel, who published it, included the paper.

Suzanne has kindly shared this paper, which she calls The Buchla Cookbook, with us.

Suzanne has kindly shared this paper, which she calls The Buchla Cookbook, with us.

This is the first time this paper has been made available online.

So I use the same sequences that I used in the 70s: four 16-stage sequences. I also still use a lot of the techniques that I developed over my years of playing the Buchla.

One of the things that I think is so special about the quadraphonic performances you’re doing is how spatially specific they are. I’m wondering if you can describe the space you’re trying to create with these performances in non-musical terms? Like, what does it look like to you, or feel like, or smell like…

Spatial control was always part of the Buchla, so from the beginning we worked in both quadraphonic space and imaginary space. You could create big, small, close, far away, all that, as part of the music. It’s different from a lot of spatial manipulations nowadays, where it’s mapped onto the music in post-production. The Buchla actually generates spatial characteristics, so it’s rhythmically in sync with the music. I use different kinds of space for different kinds of things, instinctively–sometimes it’s a continuous space, sometimes it’s a discrete space, jumping around in a different rhythm. And it’s alive. Without the space there’s nothing, because the output of this type of machine is essentially monophonic. Stereo was fabricated to spread things out over a span; it wasn’t meant to move sound. Quadraphonic in electronic language is meant to be a parameter, like pitch and volume and rhythm, so it’s really part of the music.

It’s all about the motion of it–

It’s all about the motion. I always say that, with the Buchla, it’s not about the sound, but the way the sound moves. And Don knew that. We weren’t trying to imitate a sound or make an amazing sound and then play it on a keyboard. The sound was a byproduct of the way it could move. So you have voltage control, with which you could move the sound quickly, slowly, whatever, and the sound changes with the movement.

That was something I was really struck by when I saw you perform in New York. I think I told you after the show that it felt like an ecosystem. The nature of how it was alive with so many different characters, and the chaos in it–it felt very organic to me. I’m curious what some of your nonmusical creative influences are.

Well, I have art roots. My sister is a visual artist, and I grew up in the art world. My first projects were with sculptors: Harold Paris, Ron Mallory, Joseph Robinson. Maybe people you don’t know, but Ron worked in mercury, and we did a film called Lixiviation, which then became the title of the album that Finders Keepers released—

Oh, I heard the album but didn’t know it was a film soundtrack.

Yeah, that’s where it came from. I’ve also worked with dancers. Nature and the sea are very big inspirations. One of my spiritual mentors was a photographer, Ilse Bing, who was from Germany. I met her when she was in her 80’s and I was in my 30s.

She was a mentor to you?

She was, because she was a true artist, and she worked in technology. She was called the “Queen of the Leica” and I’m the “Diva of the Diode.” She was a brilliant woman who worked in a man’s world and had this incredible edge. She discovered solarization before Man Ray, and she never got credit for it. She had a very successful career, and she was somebody that I could talk to about my work. She was an intellectual, and she always would say, “Tell me, tell me about your work!” I always wanted to talk about my boyfriends, but she kept me focused. So I had such an identification with her, as you do with a mentor. Who knows what mentoring is, or how that happens. She just was. It’s who she was.

It just happened naturally?

Yes, it happened naturally. I collect her work, so I have a huge collection of her photographs. I collected them before I even knew her. When she was 60 she stopped photographing, and it was a total crisis for me, because I was young and idealistic. I thought, “How can you?” I didn’t understand, because I saw myself as somebody who was going to go forever in my art. What I’ve realized in maturity was that she didn’t stop her art, she just shifted gears, kind of like the way I shift gears. There might be people who are disappointed that I’m not playing the piano right now, and making my romantic music, but I’m doing what I do!

That’s actually something that I wanted to ask you about. Can we talk about love a little bit?

Sure. I don’t think I know anything about it, but sure.

Well, there’s so much romance and sensuality in so much of your work, but–this was the trickiest question for me to formulate. I wanted to talk to you about love as a concept, but also romantic music and the different ways of expressing it, and whether with the compositional approach you have now, you’re intentionally moving away from a romantic expression.

Well, yes! I think when you’re young and you have all those hormones, and you’re into that trajectory of finding your prince and all that, that’s a certain energy system. It’s wonderful, but it doesn’t last forever.

Like the planet Venus ideological approach.

Right! And what you find out, or what I found out as I was older, is that I love, but I don’t love in that focused, one person or one place kind of way. It’s more open now. There’s still love, but it doesn’t have to be that–what is that–the symbolic or male/female…

Movie love?

Movie love! (laughing) I love romcoms. I love the whole idea of love, and my favorite guy, what’s his name? The British guy that does all the…

Colin Firth?

No, the British guy that does all the romantic comedies.

Hugh Grant?

Yes! I love Hugh Grant, and I don’t know why! Because he doesn’t fit any of my images of an ideal. I just like his spirit, I guess. So yeah, I did have a divorce and it was a bit of a crisis because I had the perfect marriage in a way. It really was the crystallization of the utter total fantasy of love. Then when it broke, it was devastating. At the same time, I think I outgrew that idea of love. So I’m happy, I’m not looking for anything, and I think I found it! (laughing) And I love it all. I think it’s wonderful when you’re young. It’s a rough ride–it can work synchronously, sometimes perfectly, but most of the time it’s filled with illusion and bumps. But it’s worth it.

It is worth it. If I can ask one last thing, I was wondering if you have any advice you’d like to offer to women working in the music industry, or even in the art world.

We’re on the crest of a wave right now, and it’s a very important historic time for us. I haven’t seen this type of energy since the 60s, when we had another crest of the wave. Everything is waves. So now that we’re on the crest, I say don’t forget. Go with it, be yourself, take your rightful place. If you’re looking for validation as an artist, the only authentic place to start is with yourself. You must meet your own standards of excellence, because no one outside yourself can corroborate your artistic message. Women have trouble with self confidence because they’ve been trained to believe themselves to be lesser. It’s a very insidious thing. You have to remind yourself that you’re never less than. We also need to learn how to respect other women. Because women don’t even respect women.

I think women are trained to turn on each other on a dime, and are very competitive with each other in ways that aren’t necessarily helpful.

But you know why? It’s because we’re playing in a different playing field. We used to be competing with men, and we were trying to get an edge there. We’re not doing that anymore. We’re competing with each other instead of with men; and we’re not trying to take over a man’s world, we’re creating our own world. It’s wonderful; it will be a world equal to the man’s world, and different. We’ll support each other; we just need to respect the talents and the abilities of women, and to respect ourselves also. We’re having a very important and formative moment right now. We’re making a shift amongst ourselves and in the world.

———————————————

Thanks to Suzanne Ciani, René Kladzyk, Rachel Aiello,

and Matt Johnstone for facilitating this interview.

Text has been condensed and edited for clarity.