Tim Buckley – Blue Afternoon, 1969

Guest post by Cora Walters

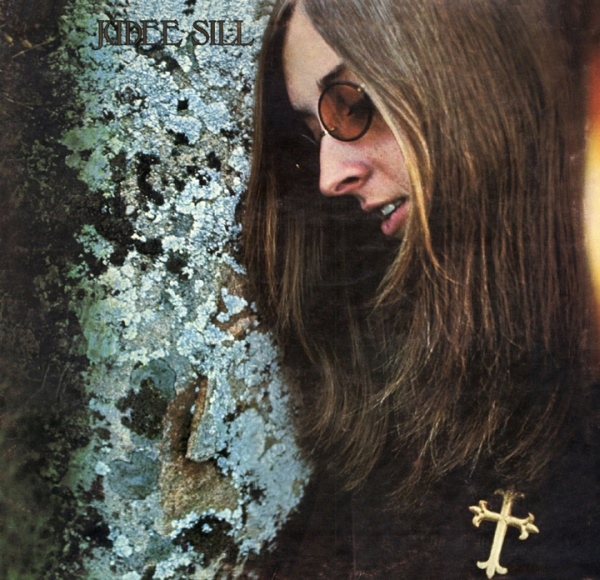

The more I listen to Judee Sill’s music, and specifically this album, the more I come to think of it as a church. The perfect soundtrack for finding your way. Her earnestness and skill as a singer and lyricist certainly rank her among the sweet sirens of the seventies–Joni Mitchell, Vashti Bunyan, Karen Dalton, Linda Perhacs, Bridget St. John, Nico–but what sets her apart is her constant craving. Surreal parables swirl around, clutching to make contact or to make sense of the world and her place in it. Each song is a hymn of her own mystical making. Even at its most baroque (“The Archetypal Man”), twangy (“Ridge Rider”), or pop (“Jesus Was a Cross Maker”), she’s driftin’ and “lopin’ along” some serious terrain–the rocky road to salvation.

When I played the album for Joe Smith, the president of the label, there was a stunned silence. Joe looked up and said, “Song Cycle”? I said, “Yes,” and he said, “So, where are the songs?” And I knew that was the beginning of the end.