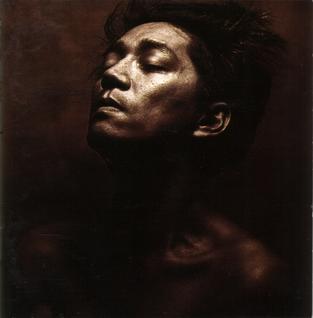

After learning on Tuesday afternoon about Franco Battiato’s death at the age of 76, I spent a lot of the past two days trying, for the first time, to take in his body of work as a whole, to whatever extent that’s possible. It’s not possible, really, as he did and made too much. Even comparisons to Brian Eno’s trajectory fall short. Although Battiato began his almost five decade long career as an avant-garde experimental musician, he went on to not just infiltrate the mainstream, as Eno has done to great effect; rather, he’s been a dominant force in defining the Italian pop world. As a non-Italian it’s difficult for me to fully appreciate the extent of his belovedness and omnipresence, but nevertheless he achieved a level of household name recognition to which the outpouring of love and grief on social media is a firm testament.

Battiato began making music with a series of excellent and challenging records which shifted between leftfield electronic experimentation and pure acoustic minimalism, before trying his hand at post-prog, new wave, modern classical, and eventually Europop stardom (highly recommend his performance at the 1984 Eurovision contest with longtime collaborator Alice). Up until recently, I had only ever experienced his work in small pieces: his singular 1974 Clic, which places his avant-garde tendencies firmly in conversation with his Krautrock contemporaries; his 1977 self-titled record of dogmatically minimalist piano; his 1992 opera Gilgamesh; his 1994 choral mass Messa Arcaica, which made its live debut in Saint Francis Basilica in Assisi; fragments of his decades-long collaboration with Giusto Pio; his contributions to personal favorites like Prati Bagnati del Monte Analogo and Medio Occidente. In trying to look at his catalog from the top down–202 releases, 358 appearances, 758 credits, according to Discogs–I thought a lot about which record readers of this blog might like to hear if they were unfamiliar with his catalogue, but also about which records of his I enjoy listening to over and over, which are the warmest and most accessible. I’ll be honest, a lot of his pop work feels somewhat alienating to me as an American–not just because his notoriously brilliant lyrics, ranging from wry social commentary to more esoteric and occasionally religious themes, are mostly in Italian and so are lost on me. Tonally, too, many of his pop modes feel extremely European in a way that my pop sensibility just isn’t attuned to.

But La Voce del Padrone is an exception, and as the first Italian LP to sell more than a million copies, it also marks a huge turning point in Battiato’s career. It was his third foray into the pop world, after L’era del Cinghiale Bianco and Patriots, and of the three it feels, to me, like the one in which he most virtuosically stuck the landing. Though there are still some gentle post-prog inflections around the edges, Padrone is a new wavey synth pop record through and through, and it’s dotted with the spacious and euphoric tracks that feel destined for scoring movie credits. (Every time I hear the driving guitarpop of “Cuccurucucu” I fantasize about a version of Flashdance in which Jennifer Beals’s iconic dance training montage is scored by Battiato instead of Michael Sembello’s “Maniac.”) And though Padrone is irrefutably Italian, Battiato remains in dedicated dialogue with extra-national influences: he quotes Dylan in both “Bandiera Bianca” and “Cuccurucucu,” the latter of which is a riff on huapango classic “Cucurrucucú Paloma” and includes some funny nods to the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Chubby Checker. I also can’t help but hear the dry, rolling cheekiness of Eno’s Taking Tiger Mountain all over closer “Sentimiento Nuevo.” There is, in short, plenty here for American ears.

The music world has lost a visionary in the true sense of the world, an oddball genius who managed the rare feat of being unabashedly himself while achieving megastardom. Thank you for everything, Franco–you will be dearly missed.

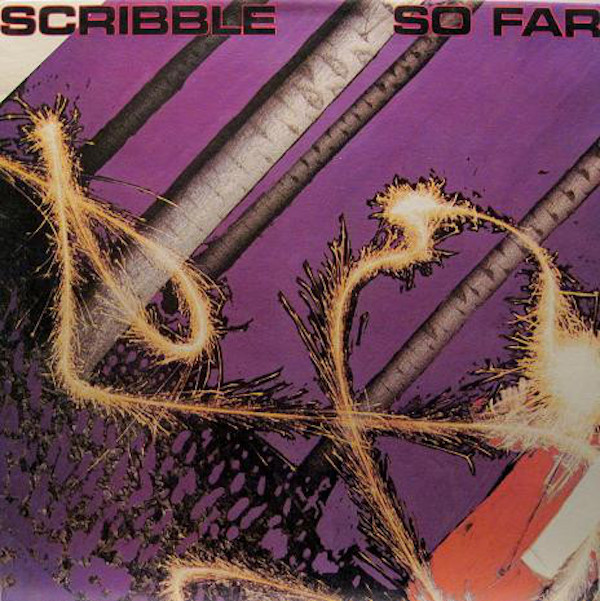

Scribble was a short-lived project of Australian musician and songwriter Johanna Pigott, formerly of punk band XL Capris. Acting as lead vocalist, guitarist, pianist, keyboardist, songwriter, and producer, Pigott recruited her partner Todd Hunter for bass and keyboards, as well as a slew of session musicians. She eventually dissolved Scribble to focus more on her writing, and went on to rack up many songwriting and screenwriting credits, including Keith Urban’s first single, “

Scribble was a short-lived project of Australian musician and songwriter Johanna Pigott, formerly of punk band XL Capris. Acting as lead vocalist, guitarist, pianist, keyboardist, songwriter, and producer, Pigott recruited her partner Todd Hunter for bass and keyboards, as well as a slew of session musicians. She eventually dissolved Scribble to focus more on her writing, and went on to rack up many songwriting and screenwriting credits, including Keith Urban’s first single, “