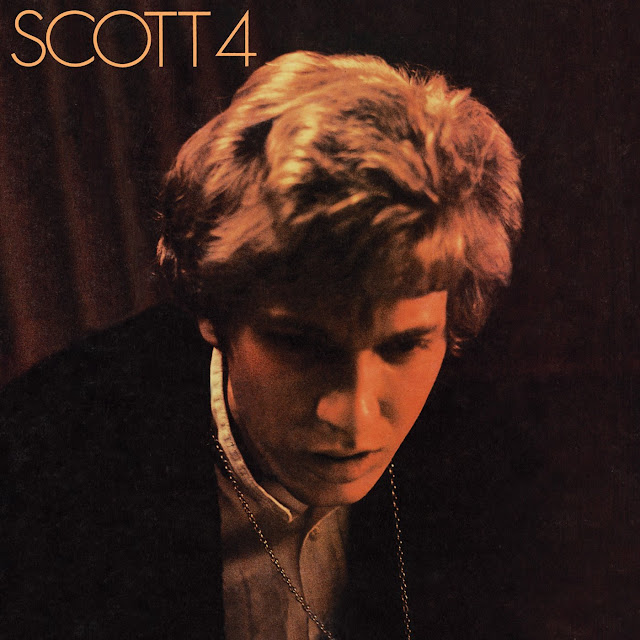

Very deep love for this record, and a very big crush on Scott Walker (no, not that Scott Walker). Walker’s career has been wholly singular, and it’s impossible to succinctly sum up him, his work, or the thematic ties between such seemingly disparate records–the only way to make sense of it all is to listen. Walker started out in an LA-based pop trio called the Walker Brothers, though confusingly Scott Walker was born Noel Scott Engel, another member of the group was named John Maus (no, not that John Maus), and all three used Walker as their stage names—though for Scott, it bore out over a long and strange career. The group attained enough chart success in the UK that they were briefly a sort of inverse Beatles export, with screaming mobs of fans and a Tiger Beat cover to prove it.

As their brief window of fame closed, Walker embarked on a series of solo records, all called Scott, and all vessels for dark, heavily orchestrated and meticulously arranged pop. Though the music felt traditional and baroque enough to be almost regressive—this was the 60s, after all—the subject matter of the songs was dark and heavily referential. Walker wrote about Stalin, venereal disease, poverty, addiction, child abuse, and Bergman movies, and he sung the songs in a theatrical, almost Sinatra-esque baritone that belied their subject matter. The joke was always on us: Walker was able to pass off drippingly sentimental delivery as sincerity while barely masking his biting cynicism. His music appealed to the elderly, to the suburban, to those who wanted to cling to tradition as the world and its sounds were being lit on fire. Walker was the Carpenters’ evil twin, with a similarly surgical approach to arrangement and production, and the Bacharach pedigree to back it up. Bowie was a huge fan. I imagine that Van Dyke Parks, sharing a penchant for thematic exploitation of traditional orchestration, was also a fan. Leonard Cohen too.

As their brief window of fame closed, Walker embarked on a series of solo records, all called Scott, and all vessels for dark, heavily orchestrated and meticulously arranged pop. Though the music felt traditional and baroque enough to be almost regressive—this was the 60s, after all—the subject matter of the songs was dark and heavily referential. Walker wrote about Stalin, venereal disease, poverty, addiction, child abuse, and Bergman movies, and he sung the songs in a theatrical, almost Sinatra-esque baritone that belied their subject matter. The joke was always on us: Walker was able to pass off drippingly sentimental delivery as sincerity while barely masking his biting cynicism. His music appealed to the elderly, to the suburban, to those who wanted to cling to tradition as the world and its sounds were being lit on fire. Walker was the Carpenters’ evil twin, with a similarly surgical approach to arrangement and production, and the Bacharach pedigree to back it up. Bowie was a huge fan. I imagine that Van Dyke Parks, sharing a penchant for thematic exploitation of traditional orchestration, was also a fan. Leonard Cohen too.

But for Walker, the real god was Jacques Brel, Belgian master of theatrical showmanship and literary lyricism, and arbiter of chanson as the world knew it. Brel paved the way for Walker’s Trojan horse smuggling of a tortured psyche under a palatable, market-friendly facade. Walker covered Brel nine times on the first three Scott records, with 4 serving as his first entirely self-written release, and it was arguably the best and strangest of his 60s releases. Despite the weight of Walker’s persona bearing down on it, 4 attains glimpses of very direct beauty—the weightless “Boy Child” comes to mind—and it readily winks at Morricone’s spaghetti Americana. Yet when 4 failed to chart, unlike all his prior releases, Walker asked his label to delete it from their catalog, tried to swing more commercial, failed, and churned out a slew of half-hearted records just to get out of contract. He then all but disappeared for twenty years, reemerging in 1995 with the left-field Tilt as incontrovertible proof that he had finally allowed his inner demons to break from the confines of polite genre. 2006’s even more mutinous The Drift was my introductions to Walker when I was 16—at the time, it was the most explicitly avant-garde record I had ever heard—so I can’t listen to Scott 4 without hearing the early inklings of sonic assault, and I love it.