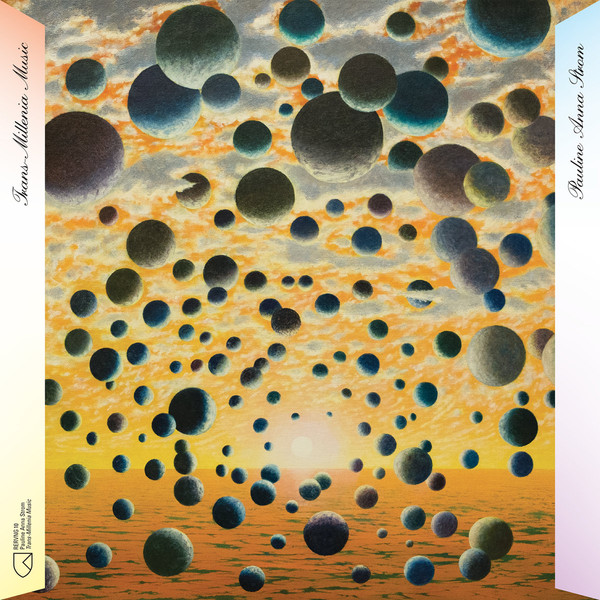

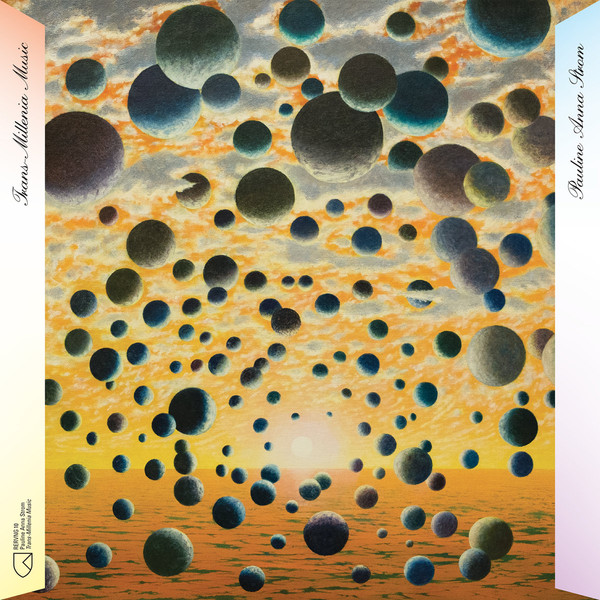

Fearlessly individualistic and fiercely independent, Pauline Anna Strom self-released a vibrantly diverse series of LPs and cassettes between 1982 and 1988. Long regarded in hushed, reverent tones as one of the finest yet most obscure composers to spring out of the West Coast home-produced cosmic synthesizer music of the 80s, Strom strove to create a sensationally heightened world of alternate reality, pulling from a past and future that isn’t quite ours. Strom’s internal vision is likely so vivid in part because she was born blind, something she feels has strengthened her musical abilities. RVNG Intl. has recently released an expansive and gorgeous 80 compilation of her work, named for her sometimes-moniker Trans-Millenia Consort, a title she uses as a “personal declaration that I have been in previous lives, that I am in this life, and that I shall in future lives be a musical consort to time.” You can buy the compilation here.

Interview by Caroline Polachek (Chairlift, Ramona Lisa, CEP)

———————————————

Where are you right now?

You mean physically where I am right now? I’m in San Francisco, at home. My studio is here. I do everything here at home at the apartment. Thank god this city has rent control!

Do you live near a park, or nature at all, or are you mostly indoors? I ask because I’m very curious what your relationship with nature is like.

Well, when I was married and had a husband that could see and we drove places in the car, I’d spend time at the ocean and different places like Muir Woods. Since I’m on my own now I don’t get to go as much. But my deeper connection with it is in my mind, and my brain, combining experience in time gone by and what I hold onto, and what I can sense and feel. Does that make sense?

Absolutely. Are there any specific sonic memories of nature you go back to a lot?

I used to take a recorder, a Sony TC-D5M, and headphones, and record wherever we were and bring the sound and process it, whether it was the ocean, or just the air and trees, or animals, those kinds of things, and just give it space to breathe and to live in with a lot of different effects by giving it the depth and precision of timing. Does the make sense? A challenge to me would be now to create those same sounds, not through sampling or recording, but actually creating them using synthesizers, using all the parameters, time signatures, wave forms, frequencies, everything like that. The challenge is to create sounds, create water. Not just the wave, but to create water—does that make sense?

Well, as a listener I get the impression you’re already doing that in your work—for example, very literally with the Aquatic Realms record.

All of the sounds that you heard in Aquatic Realms were all created sounds on the Prophet 10.

Yeah, I could tell, almost because they seemed kind of uncanny. The first thing that hit me was an awareness of “Okay, she’s recreating nature with what at the time was very new technology.”

Mmhmm!

But the more I listened to it, it made me think about how the deep sea world actually sounds quite like electronic music in the first place, which then flips inside out again when you remember that nature is actually informing technology development, whether we’re conscious of it or not: deep sea creatures with all the lights, or geometric perfection, efficiency, all that. It sent me on kind of a spiral.

Yeah!

But your records preceding Aquatic Realms almost seem to exist in a kind of pre-nature place, or post-nature place, like plants, animals, trees, human voices don’t belong in that world. It’s too pure. I imagine a primeval earth, before life exists or after it’s been destroyed.

That’s the way I think. Usually I create things with my mind and then try to create them in sound as I go, but what you’re expressing is exactly right. I’ve never felt at home in the present time. It’s always like, “I’m here but I’m not in the right place.”

I think a lot of people feel that, they just don’t manage to find an escape. Do you ever feel like that’s the task as an artist, to create the place you feel at home?

I think so. I’m the kind of person who could go to Mars and be perfectly content as long as I had my animal, my music, perhaps a mate, someone I could love, and be able to read.

What kind of animal do you have?

She’s a Cyclura, a lizard.

Does she make any sounds?

The closest she’ll come, and I’m going to have to try to catch that sometime, is you know, Mommy picks her up and carries her around and she’ll go (whispered) “hhhhhheh” (laughs). Like, “This woman is dragging me around like a rag doll!”

She sighs! A sighing lizard!

Yes, she does! That’s as far as her capability goes. But I believe that these sounds…probably I could even get a stethoscope and listen to her heart, record that kind of thing too, the blood flowing through her body. But what I’m trying to say is that I’m not really in tune with present time and modernity as we know it today, but the the far flung past, distant future, the primitive.

But both those states only exist in our imagination, and in that way could you say they’re just extensions of yourself?

Yes. Yeah, I do.

You mentioned earlier the idea of “timing”—the way you might handle samples within time, and that’s something that feels quite unique about your work. I come from a pop background where the dynamics, the changes between patterns, is what creates excitement or emotion. You get big moments of impact and movement. But the thing that struck me about your music is how you’ve so completely smoothed out dynamics, and the changes really sneak up on you like watching weather. It doesn’t guide the listener the way pop does.

Right, right. In other words, you follow a formula.

Not a formula, it’s just a different language—almost like a dance using dramatic synchronized gestures verses a wash of ambient ones.

Ah, I get it.

It’s a different way of using the same tools. But what I’m curious about in your work is how you use synths like voices coming in and out to create a fairly static picture that always has a very even amount of motion going on—it never goes dead or peaks; it’s like watching an aquarium. And with that in mind, going back to the idea of timing—what does it feel like for you when you’re working with a single layer of sound and deciding its timing? What’s your relationship with knowing when to bring things in and out?

It’s just kind of intuitive—I let it flow and it just happens, without a preconceived way of doing it. It’s right. I live in it. When I’m creating it I live in it, I surrender to it and become it.

Have you ever worked with voice?

Just my own. I’ve worked a lot with processing my own voice. There are a few where I used heavy effects and allowed my voice to come from different areas, and I also sometimes mix with my headphones on. But yes, just allowing the voice—not in the way you would think of singing, but making it like an instrument.

What about synths as voice?

Oh! I don’t have any problem with that at all, especially because there’s so much we can create. In those recordings I used a Prophet 10, a DX7 and an E-mu Emulator…that was all analog equipment. But now I can do all the same things digitally, so I’m learning a whole new world where I’ll have much more control—but it’s structured in a totally different way.

What’s your setup like now?

Right now I don’t have much, just a Korg Kross and an Ultra Novation, and the thing with these machines is (sighs) the manuals. I want the parameters manuals and the operations manuals, and of course there’s no speech driver in the machines. I wish those companies would put something like that in there, because everything is on a display so I can’t get really deep into something the way I want to. So I have a friend that’s patiently, verbally recording the manuals for me.

Would you ever make those audio manuals accessible to the public?

You can download them from the companies once you do the warranties and all that, but then they’re secured. I wanted to download the manuals into my Victor Reader Stream, which is a device made by Humanware. I wanted to download it into my Victor so I could go through it page by page, but the manuals don’t transfer across devices. So that’s why he’s verbally recording it for me. I don’t think I could upload it for the public, but I do think if they made speech drivers for the machines to allow for a setting you could use as you scroll through the display, it could tell you what’s there and how to get to things. And that wouldn’t be hard to do.

Would you ever collaborate with a synth company to make a system like that?

Yeah, I would. See, with the device I use, I download lots of books from the library and bookshare, podcasts and news services. I can do all that on the Victor and their manuals are burned into the software internally. So when I got the Victor and learned it, I went through the user manual and it showed me all the correct keys with error messages and everything. If they can do that then surely it must be possible with other electronics. But back to music! I really do like the Korg, and another thing is I wanted a workstation. I like it, I really do, and it’s great to be able to save everything on the SD cards.

Is it at all like using an 8-track?

Yeah, my Yamaha QX1 was an eight track recorder. It was digital but it used a floppy disk! (laughs) But I’ve alway been one to save things. I don’t feel comfortable unless I’ve got that backup, like, “I’m going to lose it all!”

At the time, all this gear, especially the digital stuff, was brand new territory. How did you first start experimenting with it and learning it?

I fell in love with the Prophet 10 right away. After that there was the CS80 then the DX7…I’d learn as I’d go. I’d learn through repetition—you could explain something to me technically and it’d probably go right out of my head, but when my hands start doing what I know to do I learn that way. And I just experimented and gradually worked through it all.

Do you ever have dreams where you’re programming?

No, but I get lost emotionally, and I work at night. I live downtown and it’s noisy, so the quietest time to do anything, when the energy is slower, is at night. So I’m a night person because of that, in a lot of ways. But if I start at six in the evening, it could suddenly be six in the morning and I wouldn’t even be tired. Time sort of stands still. It goes by and you don’t even…you probably experience this.

Yeah. I experience it with editing especially, where you lose so much time listening to long stretches over and over again to just make one adjustment to one little thing.

The way I did it all—I guess you classify it as overdubbing? I never know what the completed piece is going to be. I just start with an idea and work with it, then build upon it track by track without a plan, just going on what feels right. That’s how I basically did it, and how I’ll do it again once I go digital. Did you ever work with a TX816?

No, what is it?

Ahh, Yamaha only made a few of them. I’ll tell you, when I eventually make money, the Yamaha—they have a wonderful workstation—that would be the be-all-end-all for me. When they came out with the DX7 they also came out with something called the TX816 which was a big box and it had eight little DX7s. You controlled them through the DX. I’m hoping that I can figure out a way in time, cause I made a lot of sounds for the 816 and you played them through the DX7 and the keyboard…and, oh, I got creative! I got lost. There are some really unique sounds in that thing. I can get lost in creating sounds. Equally intriguing is getting lost in the sounds, and that thing really allowed you to build and build. In other words I would create a sound but it wouldn’t be just one—it would go through all eight boxes and allow you to create some kind of sound you’d never think of. God, I love it, I love that stuff! It’s almost like a drug.

Speaking of drugs, you do have a couple tracks—

(laughs) Oh yeah, I know where you’re going…

I was just curious because some of it feels bleak, and I wondered if you were being critical of drug experience or people’s reliance on them—

You’re talking about Plot Zero and “Mushroom Trip” and those pieces? I wasn’t being critical. I looked at those pieces like a mind trip without chemicals.

Were you going based on other people’s descriptions or your own memories?

My own! (laughs) There’s a very short piece—I’m sure it’s lost, it’s not out there—it’s called “Domestic Peace.” It’s probably all gone, because you know the tape deteriorates, but I put a plate on the table, utensils, and I set all my effect so you’d feel like you were setting that plate down in a vast canyon.

Wow.

And I set the utensils, then I stir fried some vegetables and added that, then poured a glass of water, but then made the water seem to go from one side of the room to the other, and then I added in a baby voice (makes baby voice), and the only music in the whole thing was synthesizer flute very subtly in the background at one point. But what I was creating was a scene. I’d love to do more of that, create different scenes. I remember once a friend of mine was having a Halloween party and he knew I had an imagination, and he wanted a piece for the party, and he called me 24 hours ahead of time so I had to put it together very quickly. I created a heartbeat and a few gongs on the Prophet. They were going to have a guy laying in a coffin, and I created an attack on a woman. I did the voices of both the male attacker and the woman, and then to decapitate somebody I dropped a cabbage in a bucket of water. I created this whole scene and they loved it, but other people I played it for either hated it or were fascinated. But that’s something I want to get back into—making scenes and elements and scenarios with sound. There’s a lot in my mind I could come up with like that.

How do you feel about the potential for virtual reality or interactivity, the fusing of that technology with music?

I think it’s perfect. I’ve had this preconceived idea in the back of my mind. I’m not a live player, but I think I could interact with things like that. Not the same as a concert, but like what you’re describing. My lizard’s name is Little Soulstice, with a “u,” like “soul.” I could picture this project involving lizards and reptiles in a soft way, with them floating in the air in virtual reality. Little Soulstice floating through the air, creating sound and music and light. There’s a lot that could be done with that kind of stuff.

You mentioned light. What’s your relationship like with light?

I see things in my head. I dream in color. I see things and know how they should be. I just…know. If I go out on the balcony right now I know the sun is there because I can feel the heat. The blindness to me is a nuisance more than anything.

When I listen your work I imagine an immersive 3D environment, which I know isn’t an accident. You’re so tuned to environmental sound. The kind of focus it must take to create the depths of these environments—

I think I know where you’re going. On the album with more Asian material, Japanese Impressions, it has those pieces “Tea Garden” and “Warriors Of The Sun.” I’ve never learned or experienced any culture or nationality of music, but I can sense how to do it myself. Does that make sense?

But you must have listened to music from other cultures, no?

I mostly listen to classical. A lot of Bach, Chopin, a lot of early music too. Gregorian chant, a lot of very early medieval stuff.

So many electronic musicians specifically reference early music and Bach. Why do you think that is?

Maybe it has something to do with the frequencies and the harmony? I’m not sure. There must be a connection in that way.

There’s something futuristic about—

It’s timeless.

Beyond being timelessly enjoyable, something about the intervals just feels…

Ooohhhh yeah. Speaking of timing, when I had all that equipment, I didn’t just look at the Prophet or the DX, but everything at once. I had a whole rack of that stuff, but I looked at the whole thing as one big synthesizer. I’d use the effects a part of the composition. With the QX1 when you edited, creating intervals that weren’t even played but just layered using effects, the whole setup is one big instrument. I did it all as part of the composition. It’s so expressive, there’s so much you can do. And now of course with these machines, everything in that rack is software now—you can do all that and it’s all in that little thing, in one keyboard. You don’t need tons of stuff like you did before! My hangup about computers, though, and you can correct me if I’m wrong, is the obsolescence that’s built in. I want a solid state machine that I can rely on fifteen years from now. Even if I got something else, I want to be able to transfer work…you see where I’m going? That’s what I resent about all of this.

That’s a good point. A violin you can pick up fifty years later and it’s still a violin.

Yeah. We’re forced through obsolescence. I don’t have a smart phone and I don’t want one. I have a little flip phone. We’re on a landline right now, plugged into the wall. But I can’t do this “every three years you gotta buy the latest thing”…when it comes to making my work I need something I can rely on, that I can trust, so I’ll never have to throw all my past work out the window. Ugh! That’s a big part of my upset with the whole thing. (laughs)

I’ve been screwed by that a few times, and yet I keep coming back to it without a second thought. It’s something everyone takes for granted too.

You mentioned that one of the pieces you heard, Aquatic Realms, where you hear the water dripping? When I created the water dripping on the DX, when I created water dripping with my fingers—you’ll think I’m crazy, but I could feel the texture of the water in my fingers as I played. You can’t do that on a computer. You can’t feel that kind of connection on a computer.

They do make very good midi controllers now that give you the contact a piano or a nice synth would have.

Mmm.

But zooming out a bit, I wanted ask you about the RVNG reissue. How do you feel having the music repackaged for a new audience?

I’m very happy with it. I think it’s a beautiful job and I have no complaints about it. But you know, maybe because the label is out east and I’m here, I know it’s real but I sort of feel a disconnect. Nobody’s fault, but the reissue is a reality out there, but not for me. When I can begin to create new things, that’s where I connect with reality.

Do you have plans for new music?

Ohhhh yeah, once I can get these manuals!

———————————————

Thanks to Pauline Anna Strom, Caroline Polachek, Matt Werth, Brandon Sanchez, and RVNG Intl. for facilitating this interview. Text has been condensed and edited for clarity.