One of the hardest and best parts about writing this blog has been running up against records that feel impossible to write about, avoiding them for months or even years, and then eventually writing about them anyway. This is exactly that kind of record, and fittingly I’ve been putting it off since day one: its influence is too far reaching to properly recount, it’s too elegant and precise to accurately describe, and I feel too gooey about it, too pierced to possibly set my feelings aside and attempt objectivity. I think that’s alright, though, because Plux Quba is too perfect not to share.

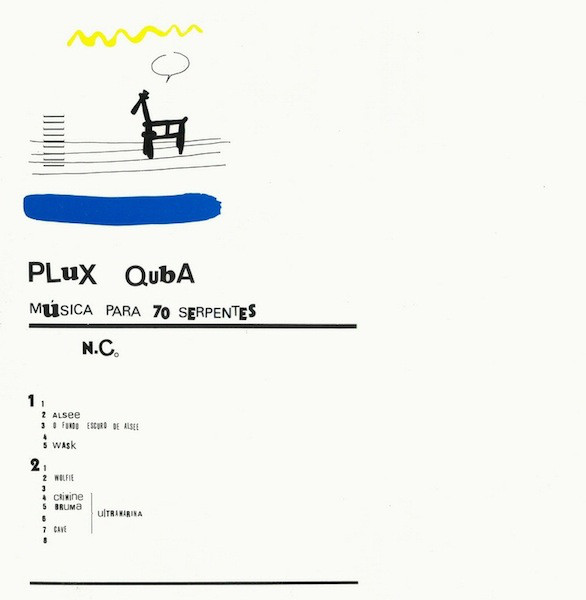

The story starts with a familiar format that, coupled with incredibly prescient music, feels like the foregrounding for a hoax. In 1991, Christoph Heemann brought a copy of Plux Quba to (from what I gather was) an informal listening session with Jim O’Rourke, Jan St. Werner, C-Schulz, Frank Dommert, and George Odjik in Köln, Germany. It was music without context, laboriously made with just an Ensoniq Mirage, a Fostex 8-track tape recorder, and an early 8-bit sampler loaded with pre-recorded, highly modified samples of things like television, radio voices, and a melodica. The story goes that everyone present was floored by it; O’Rourke so much so that when he launched Moikai, his label dedicated to minimal and electronic music, Plux Quba was his first (re)release, remixed and remastered by Portuguese guitarist and composer Rafael Toral. Since then it’s been reissued a few times, most recently by Japanese label Inpartmaint Inc, and while it has had incredible bearing on two decades of experimental electronic music, it seems that Plux Quba hasn’t yet received the widespread acclaim it’s due.

Several reviewers have said that Plux Quba takes inspiration from Robert Ashley’s Automatic Writing. I don’t know if that’s directly true, but I like to think of this record as hermetic, like the music of Charanjit Singh or Woo, bearing the kind of brilliance that often does write its own spontaneous language. It’s much too deliberate to be called an accident–Canavarro was already a well-seasoned musician by this time. And yet despite being recorded at home on very dated, simple equipment, it seems to exist outside of time. Having witnessed the subsequent deluge of glitch music and its offspring, this still sounds truly alien and exploratory, a kind of sonic alchemy. It’s more abstract than what I typically post, so if you typically gravitate towards things that are lyrical or poppy, I would absolutely encourage you to start here, preferably in headphones–though, for what it’s worth, Canavarro himself instructs on the back sleeve that this record must be heard “1. through speakers that are as far apart from one another as possible, and 2. starting from A-5, at a low volume (‘Wask’ and side 2).”

It explores similarly incandescent territory as Canavarro’s remarkable split with Carlos Maria Trindade, often employing the same textural palette and manipulations of vocal samples–slicing them up, stacking them precariously, drawing them out into ghost whispers, and running them backwards. But with a longer playtime and no collaborators, Canavarro is able to fully world-build, perhaps to even create something that feels more circular and complete. Comprised of 15 vignettes, mostly between one and two minutes long, not all of this record is unabashedly beautiful. Parts are deliberately jagged (“Alsee”), faltering (“Untitled 1”), or shrill (“O Fundo Escuro De Alsee”), but it’s precisely their inclusion that allow the record to reach sublime, sparkling heights. The stumbling, out-of-tune baroque of “Crimine” comes to mind–even here, after two and a half minutes of uncertainty, the song abruptly shifts to a perfect, crystalline music box lullaby. The record most perfectly exemplifies its own restrained breed of heartbreaking on the final track, Untitled 8. Slowly building, gently pulsing synthetic marimba, a veil of processed, indistinct whispers, a faraway oboe, and a ship’s bell that, when fully faded out, leave you perfectly positioned to restart the record.

If you’re interested in learning more about the recording process, in my Googling I found out that Fond/Sound has lovingly translated a rare interview that Canavarro gave to Fernando Magalhães into English. You can read it here.